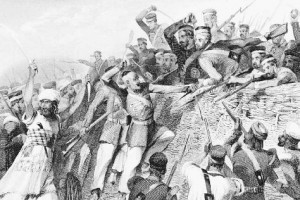

On this day in 1857 in Meerut, India, three infantry regiments of Indian Sepoys turned their guns on their commanding British officers. Shouting ‘Maro phirangi ko’ (death to foreigners), they killed any European in sight, burnt the officers’ quarters, freed 85 imprisoned comrades as well as 800 other prisoners and set off towards Delhi. 24 hours later, they took control of the city and declared the 82-year-old Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah II the leader of their rebellion. Other mutinies throughout the country quickly followed, and within days the incident at Meerut had escalated into a national revolt. Thus began the Great Indian Rebellion of 1857 – the first battle in India’s long struggle for independence. For over a year, the edifice of British power tottered and was nearly overthrown in what was to be the greatest war of resistance ever fought against a colonial power in the whole age of European imperialism.

The revolt had been looming for years. By the late 1700s, just as it was losing its old empire in North America, Britain’s privately run East India Trading Company consolidated its foothold in Eastern India – collecting taxes, running the government administration and overseeing the hugely lucrative trading posts. Accelerated expansion throughout the sub-continent followed. But after one hundred years of “divide and rule” policies, unwelcome evangelical Christian missionaries, a decree replacing English as the language of administration and education, ruthless taxation, extortion, racism, bullying, de-industrialisation and famine, the poverty and caste system which had afflicted the lives of most Indians in the late Mughul period had worsened considerably. This part of the world that had so recently dazzled Europeans with its riches was on its way to becoming one of the poorest. The Bengal army soldiers, or Sepoys, had once enjoyed respect from the East India Company. But by the mid 1800s, they were disgruntled by poor pay, bad assignments and limited opportunities for advancement. The final insult came when the Sepoys were expected to reload their rifles by biting off the ends of cartridges greased with pig and cow fat, substances deeply offensive to both Muslim and Hindu religions. When the new cartridges were issued in Meerut, 85 Sepoys refused to bite them. They were subsequently stripped of their uniforms in the presence of the entire Indian garrison, shackled, court-martialled and sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment. This wildly arrogant British miscalculation provoked a violent reaction as Hindu and Muslim united to fight for freedom.

The turbulent wave of rebellion initially took the British entirely by surprise, as region after region fell to the insurgents. Stretching from the great urban centres of Delhi and Lucknow through to the smallest villages, every symbol associated with British authority was targeted. As the mutiny progressed, the peasantry joined in – attacking record offices associated with tax and rent collection. But it wasn’t long before British reinforcements arrived, who responded in a frenzy of revenge. The British killed every single male adult they found in Delhi, forced the women and children out of the city, then razed to the ground some of its greatest and most sacred monuments. By the summer of 1858, the rebellion was entirely suppressed. Mutineers were tied to cannons and executed.

In an 1858 act of British Parliament, the East India Company’s rights in India were transferred to the Crown; soon after, Queen Victoria declared herself Empress of India. It was the beginning of the British Raj – the “devil’s wind”, as it was called, with its fervent racism and religious bigotry that epitomised the British Empire. But the Great Rebellion was in truth the beginning of the end for the British rule over India. Although it would be another gruelling near-century before independence was won, in the words of historian Dr. R.C. Majumdar:

It has been said that Julius Caesar when dead was more powerful than when he was alive. The same thing may be said about the Rebellion of 1857. Whatever might have been its original character, it soon became a symbol of challenge to the mighty British power in India. It remained a shining example before the nascent nationalism in India in its struggle for freedom from the British yoke.