It was a bright morning in Dublin on May 12th 1916, and a great crowd had gathered outside of Kilmainham Jail. As spring was turning to summer, a city still coming to terms with the death and destruction of the Easter Rising was being forced to accept yet more blood-letting. People near the jail on recent days had heard the terrible sound of a volley of gunfire as the firing squads ended life after life, and then watched as the black flag was raised above the building. Executions without trial, these state-sanctioned murders represented the British government’s response to the most recent attempt by Irish socialists and nationalists to break free from the shackles of Empire. With between one and three shootings per day, Dublin’s mornings were scheduled to be punctuated by gunfire for the next two months. As blunt a demonstration of the iron fist of oppression as could be imagined.

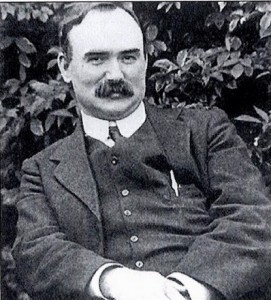

But the size of the crowd on May 12th, and the anger and outrage it displayed, was to force a rethink of British policy. Because it was on that morning that James Connolly was gunned down, tied to a chair, in the courtyard of the prison.

Connolly was born in Scotland in 1868. The son of Irish immigrants, he spent his childhood in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh; then an Irish slum. He attended the local Catholic school until just before his 11th birthday, whereupon he joined the ranks of the army of child labour that formed the lowest tier in the support system of the Great Industrial Empire. By the time he was fourteen, Connolly sought escape from the poverty of the slum and – lying about his age – joined the British army. How different would history have been had Connolly’s regiment not been posted to Ireland?

For the next seven years James Connolly was a British soldier in a country on the brink of revolution. A country he’d been raised to call his own, despite his thick Scottish accent. They were formative years for the young Connolly. Years in which he first encountered Irish nationalism, Karl Marx and Lillie Reynolds. He was to devote the rest of his life to all three… deserting the army, marrying Lillie and becoming a revolutionary firebrand. Critics of Connolly have often argued that he gave his political activism a higher priority than his family. But the unwavering and vocal support he received from Lillie, and later from his son Roddy and daughter Nora, who became a revolutionary socialist herself, tell a different story. Those closest to James Connolly shared his passion for social change and saw in him a man who might just be capable of bringing it about.

And bring it about he certainly did. No, he didn’t usher in the international socialist revolution he wrote about, but by aiming so high and urging so many others to do the same, Connolly brought radical social change to Ireland and was cited as an inspirational figure far and wide. Including by none other than Vladimir Ilyich Lenin.

Apart from his primary school in Edinburgh, Connolly was a self-educated man. He had a reputation as a prodigious reader and consumed books on political theory from all points on the spectrum. But it was the work of Karl Marx than chimed deepest with him. Connolly fervently believed that no human being should be forced to endure a lifetime of poverty and while he never truly escaped it himself, his activism paved the way for the Irish working class to begin the long climb out. He spent a few years back in Scotland after deserting the army and became involved in left-wing politics, founding The Socialist newspaper. But it was when he was offered a position as secretary to the Dublin Socialist Club in 1895 that his political activism really took off.

Within months of returning “home” to Ireland, James Connolly had transformed the Dublin Socialist Club into the ISRP (Irish Socialist Republican Party), a small but hugely influential group that was to become the template for future Irish socialist parties. Publishing the nation’s first regular left-wing newspaper, Workers’ Republic, the ISRP embodied the ideals of socialism and republicanism that were to inspire Irish revolutionary socialism for generations to come. Connolly believed in Marx’s vision of international socialism. At the same time he remained an Irish nationalist, convinced that Ireland could never be part of an international revolution until it had thrown off the shackles of imperialism and taken its place among the community of independent nations.

In 1903 he was invited to give a series of lectures in New York by the Wobblies (the Industrial Workers of the World). His pamphlets had made their way around the world and had met with acclaim from Marxists, labour unions and socialists. His stay in America ultimately lasted seven years. Active within numerous socialist groups and founding one or two himself, Connolly learnt much from his involvement with the American labour union movement and upon his return to Ireland in 1910, was in a militant mood.

With his friend and fellow-traveller “Big Jim” Larkin, Connolly helped set up the Irish Trade Union Congress. Larkin was a revolutionary syndicalist and had formed the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union – by far the most militant Irish labour union and a pivotal organisation in the Dublin Lockout. Together the two men set about planning a workers’ revolution in Ireland and formed the Irish Labour Party to help bring it about (oh, how that once mighty organisation has fallen!) In 1913 Larkin called a General Strike and the Dublin Lockout began. Initially picketing and agitating for better pay and conditions, the Lockout turned nasty when the Dublin Metropolitan Police were ordered to break the strike by any means necessary. Violent clashes erupted and Connolly responded by forming the Irish Citizen Army.

Initially created to protect workers from the increasingly brutal police attacks, the ICA soon evolved into an armed force dedicated to “an independent Irish socialist republic”. After Larkin fled to America when the Dublin Lockout eventually ended in 1914, Connolly began organising for national rebellion and sought allies within the Irish Republican Brotherhood and Padraig Pearse’s Irish Volunteers. And on Easter Monday of 1916, they began that doomed rebellion.

During his life, James Connolly published a number of books and dozens, perhaps hundreds, of pamphlets and essays. Along with Jim Larkin he arguably created the modern Irish labour movement and unionised the workforce. While he was alive, Connolly was an inspiration to many thousands, and in death he has been an inspiration to millions. Indeed, it has been said that it was Connolly’s death, above all things, that shook the Irish people from their stupor and brought about the War of Independence that would ultimately lead to the formation Irish Republic.

On the morning of May 12th 1916, with shrapnel in his chest and his ankle shattered by a bullet, Connolly was transported from a secure hospital in Dublin to Kilmainham Jail. He was carried on a stretcher from the ambulance to the courtyard, pausing briefly to allow him to meet with a priest. He is said to have confessed his sins to the priest and received communion; his first religious acts since his wedding in 1890. Famously, when the priest asked whether he could forgive the men who were about to shoot him, Connolly replied “I will pray for all men who do their duty according to their lights [conscience]”. He then smiled wickedly and whispered “Forgive them father, for they know not what they do”.

[Written by Jim Bliss]

11 Responses to 12th May 1916 – the Execution of James Connolly