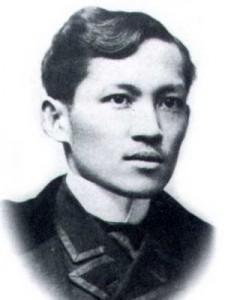

On this day in 1896, José Rizal – the “George Washington of the Philippines” – was executed by the Spanish Army following a false conviction for rebellion, sedition and conspiracy. Rizal had devoted all of his brief adult life to liberating his countrymen from the 300-year yoke of Spanish colonial tyranny. So his imperial overlords were happy for any excuse to get rid of such a firebrand, even though Rizal had not participated in the nascent armed uprising; believing in non-violent resistance, he had even criticised the rebels. For Rizal was a man of words – but his were so incendiary that he gave birth to the Philippine Revolution with even more force than a gun or a sword.

The most celebrated and radical Ilustrado (the “enlightened” Filipino class), Rizal was a genius and recognised Renaissance man: doctor, poet, writer, sculptor, painter, musician, architect, historian, teacher and proficiency in twenty-two languages were some but by no means all of this polymath’s talents and skills. His political ideas were forged by his extensive European education in Madrid, Paris and Heidelberg. It was during this time that Rizal published several essays and editorials opposing Spanish colonial tyranny and clergy despotism. But it was his two daring novels – Noli me Tangere and El Filibusterismo – which gave rise to a national Filipino consciousness. “I have endeavoured to answer the calumnies which for centuries had been heaped on us and our country,” explained Rizal of his literary intentions. “I have described the social condition, the life, our beliefs, our hopes, our desires, our grievances, our griefs; I have unmasked hypocrisy which, under the guise of religion, came to impoverish and to brutalize us.”

Banned by the Spanish, copies of these two novels – published in 1886 and 1891 – were smuggled into the Philippines and read stealthily by the Ilustrados. The impact was, well, revolutionary. Like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin – which Abraham Lincoln cited as one of the triggers of the American Civil War – Rizal’s novels would spark the flames of the Philippine Revolution. Furious Spanish officials deported Rizal to the easternmost island of the Philippines for four years, but when an uprising broke out in Manila, they nevertheless accused Rizal of initiating it. Whilst en route to Cuba, he was returned to Manila and arrested for revolutionary agitation and convicted of treason. The Spanish were so fearful of a public mutiny that they executed Rizal an hour earlier than scheduled – but 30th December 1896 was to be a pivotal turning point that activated a full-scale revolution, and the anniversary of Rizal’s death is today commemorated in the Philippines as a national holiday.

Before the late 19th century, “Philippines” was only a geographical term for a vast archipelago of some 7,000 islands. The Philippine Revolution was borne of a consciousness by the inhabitants of these islands that they could be one nation bound by a common culture, history and destiny. Rizal’s execution served to broaden this consciousness. The Philippines was the first country in Asia to stage a national revolution and declare its independence on 12th June 1898. By virtue of his daring vision and the forcefulness of his language and imagination, Rizal not only pioneered the Philippine national consciousness – but his martyrdom would also send a trenchant message to the colonial powers throughout the vast region of Asia.

Pingback: Colonial tyranny | Bertobeyweddin