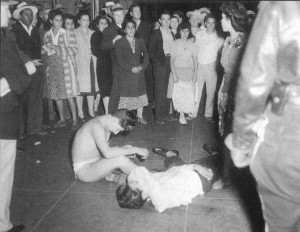

On the night of 3rd June 1943, as American men of all ethnicities shipped off to service in World War II, the city of Los Angeles witnessed a violent outbreak of racism when a group of fifty U.S. sailors ran amok viciously attacking any Mexican-American youths they found to be wearing zoot suits – those long vibrantly-coloured jackets-and-pants so beloved of ‘40s black jazzers. These young Hispanic victims – deemed by the sailors to have been too provocatively unpatriotic by wearing such flamboyant garb during wartime – were stripped, beaten and even pissed upon. Their ‘inappropriate’ clothing was then ritualistically burned. For almost the next two weeks, thousands of servicemen-on-leave joined in the hunt for young zooters, fuelled by a racist local press that lauded the “cleansing” of “miscreants” and “hoodlums”. A few days into the riots, Los Angeles city council banned the wearing of zoot suits – not to protect the victims, but because such clothing had become viewed only as a “badge of hoodlumism.” Soon even civilians joined in the attacks. Thousands of whites roamed the streets ministering summary justice – taxis even provided free transport to the “mass lynching”. The Los Angeles Police Department, meanwhile, turned a blind eye to the attacks and instead indiscriminately arrested hundreds of Mexican-American youths. Finally, the citywide rampage was brought to a halt by California’s military chiefs-of-staff who, understanding at last the gravity of the situation, confined all men to their bases.

The so-called Zoot Suit Riots would expose the polarisation between White America and the growing Mexican-American community, and would intensify the USA’s collective wartime paranoia; a grand and selective paranoia that would permit Americans to treat all non-whites as a threat to homeland security.

But why had the behaviour of these young Zooters caused such extreme reactions among white Los Angeleans? Well, the previous two decades had seen such a large influx of Mexicans into the Los Angeles area that their children were now growing up disenfranchised both from their own culture and from American culture. Caught between two worlds, these socially disadvantaged second-generation young Mexican-Americans had created their own dialect, named themselves ‘pachucos’ and had adopted the flamboyant zoot suit from the black jazzers as a peacock-like badge of their own marginalisation. Unfortunately for them, while most Americans across the colour line considered the zoot suit garish and inappropriate at best, at worst, some Americans considered such garb to be an affront to that unwritten code of segregation; a code which demanded racial minorities at all times act discreetly, decorously and deferentially. In this context, we can soon see how, for the rioting servicemen, destroying the detested zoot suit was as much a show of power designed to reassert the norms of white supremacy as it was an expression of wartime patriotism.

The Zoot Suit Riots triggered similar attacks against zoot suit-wearing ethnic minorities in Chicago, San Diego, Detroit, Philadelphia and New York, and became an international embarrassment for the United States. However, the committee set up to determine the riots’ causes concluded that it had been delinquency, not racism, which had been the main the factor. We know that’s a barefaced lie, but if we’re to reduce the victims to mere delinquents, well, let’s give them their due: as the first fashion-led youths to be associated with rebellion, the zooters’ influence would reverberate profoundly for future generations of disaffected teenagers. Indeed, the riots would spawn a powerful breed of civil rights leader, including a young zooter pimp known as Detroit Red whose experience when the fighting spread to New York was pivotal in his transformation into Malcolm X. Moreover, the Zoot Suit Riots was the precursor to the widespread moral panic over the nation’s juvenile delinquents which deepened after the war and heralded the birth rock ‘n’ roll. Uh oh!

Pingback: 1930-1950 Mexican immigration « immigratepolicy

Pingback: The fire this time yet again and again | CIRCUSMAXIMO