In the early hours of the morning on June 4th 1989, the Chinese military began a brutal crackdown of the protest movement that had seen up to 100,000 people camped out in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square for more than a month. What had begun, back in April, as a series of small student gatherings to mourn the death of Hu Yaobang – the erstwhile General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party who had been expelled for his vocal support of political reform – had, by June, grown into a mass demonstration of civil disobedience by a number of disparate groups.

More than twenty years later we should be aware that not only do the events of June 4th remain a taboo subject within China, they are significantly misunderstood outside the country; without a doubt, the version provided by western media is better than the total information blackout instigated by the Chinese authorities, but it’s nonetheless misleading. In fact, even the title of this article – “The Tiananmen Square Massacre” – is a misnomer. Sure it’s a handy catchphrase, but it illustrates the inaccuracy and misunderstanding that surrounds the events of that tragic day. As James Miles, a BBC correspondent in Beijing at the time of the massacre, was to later write, “I and others conveyed the wrong impression. There was no Tiananmen Square massacre, but there was a Beijing massacre.” For while it is true that the bulk of the protests occurred within Tiananmen Square, the bulk of the violence occurred elsewhere. This may seem like a trivial point, but it is indicative of the fact that the full story of what happened is not well known either within China or elsewhere.

Part of the reason for this is, of course, the totalitarian nature of China and the effective media controls put in place by the government. But it’s also partly to do with the sheer complexity of the events and the fact that they do not fit within the convenient “evil commies crush pro-democracy students” narrative favoured by western news sources. Which is not to suggest that the One True Version can be found within the text you are currently reading. Such a claim would be beyond presumptuous. No, the purpose of this short article is twofold; firstly to commemorate those who risked their lives – and in many cases paid the ultimate price for that risk – by pitting their voices against the guns and tanks of a totalitarian government. We salute their breath-taking bravery. Secondly, to remind ourselves – if such a reminder is needed – that even in the “freedom-loving, liberal west”, the version of world events we are fed often comes with a specific agenda. Or at the very least excludes elements that might add inconvenient complications to a story.

One of the more fascinating misconceptions about the Tiananmen Square protests is that they were exclusively “pro-democracy” protests. While that was certainly a central element, it is a long way from the whole truth. It’s true that the initial gatherings mourning Hu Yaobang had political reform and greater democracy at their heart. And it is also true that pro-democracy elements formed a significant part of the larger protests and were the most vocal; though there is a suggestion that the western media tended to exaggerate this impression by consistently focusing on that issue, to the exclusion of all others. However, the pro-democracy element was but one strand of a coalition that – paradoxically – also included elements who felt that the economic reforms of the 1980s had been too extreme and had happened at too fast a pace. As Wang Hui, a Beijing university professor, said of the protesters… “their hopes for and understanding of reform were extraordinarily diverse”.

By the early 1980s reform of the Chinese economic system was underway. At the same time the government was determined to maintain the political status quo at all costs. Initially these reforms were universally applauded both within China and overseas. However, by the mid-80s problems were beginning to emerge as government price controls began to bump up against market mechanisms and government employment policy began to disintegrate. Previously, university graduates had been guaranteed a job, but the economic reforms began to undermine this security. While at the same time, the friction between price controls and a limited free market sent inflation on a steep upward trajectory.

Foreign free market ideologues – most notably Milton Friedman – insisted that China’s economic problems were not a result of the reforms but were happening because the reforms weren’t going far (or fast) enough. They also insisted that a capitalist-orientated economic liberalisation would inevitably, in and of itself, produce democratic political reform. “Free market capitalism”, it was argued, “demanded democracy”. Of course, Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore seems to have demonstrated the falsehood of that claim and in recent years China has followed suit. In the words of Slavoj Zizek, the controversial cultural theorist, “capitalism no longer naturally demands democracy but works even better within an authoritarian political structure”.

In late-80s China however, the tension between economic reform and political orthodoxy was threatening to pull the nation apart. The previous decade had seen an almost four-fold increase in the university population to meet the demands of the burgeoning economy and rapid urbanisation, but the removal of many of the traditional social safety-nets was creating widespread fear and anxiety. A paradox was developing at the heart of Chinese culture, and it was this paradox that drove students onto the streets in their tens of thousands, rather than simply a demand for more democracy and political transparency. Just as was happening half a planet away in Yugoslavia, economic liberalisation was undermining certainty and security, resulting in social unrest. It would be foolish to try and portray the Tiananmen Square protests as “anti-capitalist” protests, but it’s noteworthy that the two most prevalent non-Chinese songs sung by the students were John Lennon’s Power to the People and the worldwide socialist anthem, The Internationale.

It’s important that we understand the dual nature of the protests; not merely so we may fill the gaps in our knowledge left by a media narrative unable or unwilling to differentiate between democratic and free-market capitalist reform; but also so that we may better appreciate the depth of the tragedy of the brutal military response. For as the intervening decades have demonstrated, the Chinese government has worked hard to deny both sets of demands. They have failed to significantly reform their political system so as to provide greater democratic participation or transparency. While simultaneously they have enthusiastically embraced the free-market capitalism that breeds so much economic insecurity and social division.

Back in May 1989, however, that bleak future was as yet unwritten. By mid-May the Tiananmen Square protests had reached a critical mass and rumours were sweeping the crowd that the government was preparing to listen to their demands. Mikhail Gorbachev visited the country and despite couching his words in the language of diplomacy, clearly extolled the virtues of political reform. Meanwhile rumblings had begun in Eastern Europe, and while it would still be a few months before the fall of the Berlin Wall, there was a tangible sense of hope that genuine political change was not only possible, but underway. The General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, Zhao Ziyang, visited the protesters upon hearing the news that over a thousand of them had begun a hunger strike. His speech hadn’t gone so far as to offer concrete concessions, but like the words of Gorbachev left the protesters with the clear impression that he sympathised with their demands.

What none of the protesters could have known was that it was to be Zhao Ziyang’s final public appearance. An internal struggle within the Chinese Politburo was underway and the reformers would not prevail. Supreme Leader Deng Xiaoping and Premier Li Peng were both opposed to his conciliatory stance and viewed any concessions to the protesters as likely to lead to social chaos and the dissolution of the Chinese State. So even as the hopes of the Tiananmen Square movement were reaching their zenith, a decision was being made to crush them.

In the last week of May 1989, Zhao Ziyang was ousted from his position in the Communist Party. He would spend the next 15 years – until his death – under house arrest. Simultaneously martial law was declared and the military mobilised. Years later it emerged just how close the internal power struggles had come to tipping in the other direction as certain elements of the military were sympathetic towards the protesters. Nonetheless, on June 1st the Politburo officially declared the protesters to be “terrorists” and ordered two divisions of loyal troops into the city. They were ordered to “clear the streets of Beijing” and while the order did suggest that this be done with the minimum amount of bloodshed, they were left in no doubt that if non-violent means did not prevail, they were to use any means necessary.

On June 2nd an army vehicle was involved in an accident that left four civilians and one soldier dead. This unforeseen event massively increased tensions city-wide and led to the protesters erecting barricades in a number of locations around Beijing, setting the scene for what was to come. The following day saw the first shots fired (mostly into the air as warnings) and skirmishes breaking out between soldiers and protesters, though both sides were still exercising a degree of restraint. Tragically this reluctance disappeared in the early hours of the morning of the 4th when troops of the 27th Division of the Chinese Army were ordered to disperse a crowd that had set up a barricade about a half mile from the square. It was the beginning of a massacre.

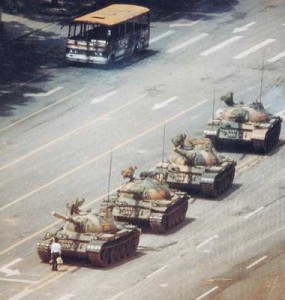

While the enduring image of that day was and will always be “Tank Man” – the lone protester standing defiantly in the middle of the road, preventing the advance of a column of tanks – elsewhere the army was less reluctant to crush those who refused to move. As a further example of just how little we know of what happened in Beijing that terrible day, casualty numbers vary from between 186 and 10,000 dead (with the Chinese Red Cross estimating up to 30,000 others injured). Over the course of that single day not only were so many innocent lives snuffed out by a brutal government determined to maintain absolute control whatever the cost, but the internal conversation about political reform that had begun – albeit in hushed tones – within Chinese society came to a premature end. Even as economic liberalisation has continued apace and the rapid industrialisation of China is leading inexorably towards ecological catastrophe, so the ability of the general populace to influence these changes has remained almost non-existent. Despite the official silence surrounding the June 4th massacre, the people of China have not forgotten that lesson in brutality and continue to live in fear of a government that refuses even to acknowledge the possibility of an alternative perspective.

[Written by Jim Bliss]

Pingback: De mythe van de Tiananmen-protesten: drie misvattingen - Het laatste nieuws over China : Het laatste nieuws over China