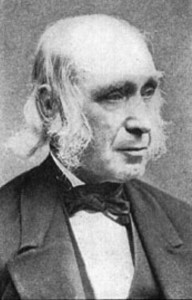

When a man is one hundred years ahead of his time, only the esteemed company that he keeps give his general contemporaries any inkling that his curious methods and zany lifestyle might be anything more than a splendid eccentricity. Throughout the Utopian life of Amos Bronson Alcott, however, this great progressive educator, social reformer, mystic and original thinker ran with such high achievers that they accepted his Utopian gush, his proto-hippy culinary pronouncements, his inability to coerce a living wage out of his brilliant ideas. Indeed, Henry David Thoreau declared him: “A true friend of man; almost the only friend of human progress.” And as one of the founders of the American Transcendentalists, Alcott – along with Emerson, Thoreau and Nathaniel Hawthorne – was part of that 19th-century “Concord Quartet” that “freed the American mind.”

So why then has the story of this bold and original thinker – arguably the most transcendental of the American Transcendentalists – fallen into the doldrums? Today, he is remembered chiefly as the father of Louisa May Alcott, whose semi-autobiographical Little Women captured the world’s imagination with its aspirational themes of self-sacrifice and self-reliance. Ah, but that very imagination that Louisa May so artfully harnessed was in fact a by-product of her brilliant, quixotic and wholly impractical father. And therein lies the root of Bronson Alcott’s problems. For although in his quest for human ascendency, Alcott was even more Emersonian than Ralph Waldo Emerson himself, this most brilliant man was utterly incapable of committing the luminosity of his conversation to paper. It seems instead that Bronson Alcott was just too busy being the group’s chief practitioner of Transcendentalism – living the dream at its most visionary, edgy and fanciful.

Unfortunately for his legacy, Alcott’s mystic philosophy permeated into his everyday with such idealistic zeal that the results were often calamitous. For example, his short-lived Fruitlands community was so Utopian, so high reaching that Alcott excluded carrots and potatoes from their self-grown vegetarian diet because their roots grew down into the earth instead of aspiring upwards towards heaven! Such half-conceived idealism brought his family and the rest of the community to the brink of starvation – Fruitlands was a spectacular failure from which Bronson Alcott learned little of practical value. His lifelong habit of taking innovative ideas past the point of sense into to ruinous extremes forced his family into a perpetually rootless poverty, moving home over twenty times and frequently relying on the good will and charity of Emerson.

Nevertheless, Alcott did enjoy notable success with his establishment in Boston of America’s first progressive school – The Temple School. Assisted by Elizabeth Peabody and Margaret Fuller, Alcott developed an experimental and highly advanced educational programme that sought to teach not by the traditional method of rote, but instead to develop the child from within. Alcott introduced pioneering methods such as organised play, imagination, gymnastics, the honour system and minimal corporal punishment. All of the aforementioned have nowadays long been accepted, but each was at the time considered to have been so unorthodox as to be scandalous. For seven years, however, Alcott’s school survived the harsh and continued criticism from the New England press and public alike until, at last, Alcott’s principles gave them the excuse they needed to shut him down. Enrolling a black girl, Alcott found himself facing a mob, who demanded her withdrawal. When Alcott refused to compromise, the school was forced to close.

Although the long life of Bronson Alcott was clearly no undisputed victory, his failures were always mitigated due to their being a product of his daring, original and unwavering attempts to restore the ascendancy of man’s spiritual nature. Moreover, the ever forward-thinking Alcott worked into his everyday life practises, ideas and influences that his contemporaries only wrote about – advances of the kind that can be found at the root of many social and education reforms that would come only much, much later. We must never judge conventionally one who has soared so high above rational distinctions in the true mystic manner, especially when one such as Henry David Thoreau deemed him the “sanest man” he ever knew.

Pingback: Keep at it… « Success!