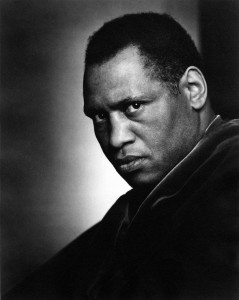

Today we pay our respects to the great singer, actor, scholar, All-American athlete and human rights activist, Paul Robeson, who died on this day 1976. In the 1930s and 40s, this son of an escaped slave was the most famous and widely respected African-American man in the world, having thrilled thousands with his commanding presence and magnificent deep baritone voice on the Broadway stage and Hollywood screen. He popularised black spirituals, and became a global hero when he learned over twenty languages in order to sing international folk songs in their original tongue. For two decades, he was the world’s most popular concert performer. But, by the time of his death at the age of 77 from complications following a stroke, he was a forgotten and broken man. For the last twenty years of his life, Robeson suffered a series of mental breakdowns and even twice tried to kill himself. How could such a brilliant and gifted world figure have been so comprehensively destroyed?

At the height of his fame, Paul Robeson made the bold decision to become a political artist. One of the earliest civil rights activists decades before the movement mobilised, Robeson was also an outspoken opponent of imperialism, capitalism and fascism and a vocal advocate for workers’ rights and international peace.

But his politicisation took a decisive turn following his first visit to the Soviet Union in December 1934. An unapologetic fan of Soviet Socialism, Robeson was moved to discover resounding similarities to Afro-American spiritual music in the Russian folk traditions. Furthermore, in Russia he found no racial prejudices. “Here, I am not a Negro but a human being for the first time in my life,” he declared to the press. “I walk in full human dignity.”

His glowing admiration for the Soviet Union earned him an amber warning with the FBI. But, after World War 2, this escalated to a full-scale Red Alert. And Paul Robeson became one of the most prominent and battered victims of the anti-Communist Cold War hysteria that swept the United States during the late 1940s and 1950s.

Whilst attending the 1949 Paris Peace Congress, Robeson declared it “unthinkable” that Black Americans could go to war against the Soviet Union on behalf of a country that had only ever oppressed them. Already tarred as ‘unpatriotic’, this statement caused an uproar throughout America. Robeson was thereafter branded an ‘enemy.’ Violence erupted at two of his concerts; dozens of subsequent engagements were cancelled as a boycott against him gained momentum.

Robeson sought refuge abroad where his popularity remained intact. But when he spoke to the foreign press about America’s mistreatment of its Black population, the U.S. State Department determined to silence him by revoking his passport and denying him a new one until he signed an oath stating that he was not a Communist and would cease political speeches overseas. Robeson refused. For eight long years, he fought to regain his passport – during which time he saw his income as well as his American fan-base dwindle to almost nothing. It became nearly impossible to hear Robeson on the radio, buy his music or see any of his films – even the widely celebrated Show Boat. All evidence of his athletic achievements and majestic career was so comprehensively erased that very little newsreel footage of him remains. A great artist and humanitarian effectively became a ‘non-person’.

Paul Robeson had always argued that he was a true American – true to the revolutionary and progressive spirit of his country’s foundations, as portrayed in the lyrics of the patriotic cantata “Ballad for Americans” which he’d popularised. In 1956, Robeson was questioned by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Asked why he did not wish to move to Russia, he replied: “Because my father was a slave, and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here and have a part of it just like you … And you, gentlemen, are the non-patriots and you are the un-Americans and you ought to be ashamed of yourselves.”

Robeson regained his passport in 1958, but it was of little consequence. Despite several attempts to rebuild his career, the damage was permanent. Shunned even by Black leaders, Coretta Scott King – Martin Luther King Jr’s widow – would later admit that Robeson had been ‘buried alive.’ His mental and physical health swiftly deteriorated, but he remained unrepentant and true to his beliefs to the end.

Robeson’s own stirring words – spoken at a “Save Spain” anti-fascist rally at the Royal Albert Hall in 1937 – serve as his enduring epitaph:

The artist must take sides. He must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative. The history of the capitalist era is characterized by the degradation of my people: despoiled of their lands, their culture destroyed … denied equal protection under law, and deprived their rightful place in the respect of their fellows. Not through blind faith or coercion but conscious of my course, I take my place with you.

9 Responses to 23rd January 1976 – the Death of Paul Robeson