The Bible, Genesis 2:20, states: “And Adam gave names to all cattle, and to the fowl of the air, and to every beast of the field”. But actually it wasn’t Adam. It was a Swedish botanist: Carl Linnaeus.

My dad was also a botanist, so since I was knee high to an orthoptera, I was aware that everything had a difficult-to-pronounce Latin name as well as its common or local name. I knew all about the splendid bulk of Sequoiadendron giganteum and the dangers of Toxicodendron radicans. But what I really wanted to do was to go to the ocean and watch the Zalophus californianus basking on the rocks.

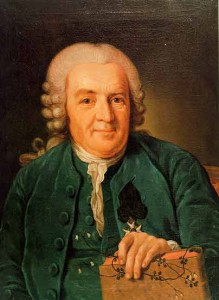

At school, young Carl Linnaeus learned Latin, Greek, theology and maths, but he wasn’t interested in that stuffy nonsense (although it would come in very useful later in his life). All he wanted to do was go outside and look for plants. Fortunately his teachers recognised his gift for science and his studies re-focused on medicine and botany at the universities of Lund and Uppsala. In 1729, aged just 22, he published a thesis on plant sexuality and began lecturing to other students. It was going to be a brilliant career.

In 1732 he made a six-month-long expedition to Lappland to study the biodiversity of the region. It would be there when stuggling to name the 100 new species of plants, mosses and lichens he identified, that the idea first came to him of simplifying the existing cumbersome system of classifying and naming living things. In Flora Lapponica, he applied his taxonomic system for the first time and realised it was so flexible and yet so specific, it could be extended to other living organisms.

There are two parts to his system, classification and naming.

Consider the zebra. We say zebra, but to Swahili-speakers all stripey horses are punda milia. But do we mean the mountain zebra, the plains zebra or Grevy’s? The Linnaean system makes classification very clear.

- Kingdom: Animalia – an animal

- Phylum: Chordata– an animal with a backbone

- Class: Mammalia – an animal with a backbone that feeds its young on milk

- Order: Perissodactyla – an animal with a backbone that feeds its young on milk that has a hoof with an odd number of toes; this branch in the tree of life includes horses, rhinos, and tapirs

- Family: Equidae – the horse family

- Genus: Equus quagga – this is the plains zebra

Its name, Equus quagga, is specific to that species alone. As with all science, things are fluid; a species’ classification is debated and revised as new data is revealed.

Which brings me to names. Consider the springtime roadside herb with crowns of white lacy flowers I know as keck. But you might call it cow parsley, Queen Anne’s Lace or wild chervil. And if you’re French you might know it as anthrisque sauvage or cerfeuil des bois. Confusing, isn’t it? As he travelled, studied and met other botanists, Linnaeus realised each species needed a universal name. He adopted a system of nomenclature only partially developed by 16th century Swiss botanist, Caspar Bauhin, which he refined and popularised into a name consisting of two Latin words. Keck became Anthriscus sylvestris.

A glorious by-product of Latin names is that they often have an innate poetic beauty and history of their own. The humpback whale Megaptera novaeangliae translates as ‘New England big wing’. While the giraffe Giraffa camelopardalis comes from the Arabic ziraafa combined with a description: tall like a camel and spotty like a leopard.

Linnaeus’ first published his system, Systema Naturae, in 11 pages in 1735. Such was its popularity that by 1768 it was in its twelfth edition and ran to 2,400 pages. The system was soon adopted by the new breed of naturalists including Captain James Cook’s expedition naturalist Joseph Banks.

So why was a system of putting species into groups and giving them universal names so important?

Species can look very different from each other and live far apart and yet still be related (the kiwi and the ostrich). Or they may have evolved similar features because of the way they feed (the thylacine and the wolf). A classification system gives scientists a logical framework based on anatomy and physiology on which they can work to reveal the truth. And without universal names how could scientists all over the world study species unambiguously and meaningfully?

Linnaeus’ classification system enabled him to think about food-chains and the interdependence of life. It wasn’t until Darwin that the complex and beautiful tree of life would begin to be explored in more detail. It would even help shed light on our own origins.

[Written by Jane Tomlinson]

2 Responses to 10th February 1778 – the death of Carl Linnaeus