On this day in 1963, civil rights leader Medgar Evers was assassinated in the driveway of his home while his wife and young children watched in horror as he bled to death on the doorstep. Lynchings were still an ugly fact of life in the Deep South, but Evers was the first high-profile black activist to be murdered. In the wake of the assassination, John F. Kennedy gave his most impassioned speech about America’s moral crisis and the need for racial tolerance. Both Bob Dylan and Phil Ochs were prompted to write protest songs in Evers’ memory. And – of greatest significance – future black leaders were radicalised and galvanised. While the assassination of such a prominent black figure foreshadowed the violence to come, it also infused the civil rights movement with a new fervour and sense of purpose. Apprehension was replaced with anger. No longer were African Americans afraid to stand up to their white oppressors. As Esquire contributor Maryanne Vollers wrote: “People who lived through those days will tell you that something shifted in their hearts after Medgar Evers died, something that put them beyond fear…. At that point a new motto was born: After Medgar, no more fear.’”

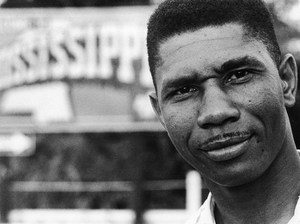

As the Mississippi state field secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in the 1950s and early 1960s, Medgar Evers held one of the most dangerous jobs in the country. In the epicentre of the Jim Crow South, Evers travelled alone through the rural back roads investigating racial violence, challenging school segregation and talking up voter registration. His wife Myrlie later recalled: “Medgar felt the deprivation of every Negro as though it were his own. He suffered with every Negro whose suffering he knew.” He was not a “personality cult” leader who dazzled with rallying speeches – but rather a “servant-leader” whose courageous fieldwork made a tangible difference to hundreds of terrorised blacks and their beleaguered communities. And that made him dangerous. For daring to confront the white world, Evers was featured on a KKK hit list as early as 1955. He and his family endured numerous death threats, but still Evers persisted with his work.

On the night of his assassination, Evers returned home just past midnight after attending an NAACP function. As he left his car with a handful of t-shirts that read “Jim Crow Must Go,” he was shot in the back. The still-smoking gun – bearing the fingerprints of staunch white supremacist and Klansman Byron De La Beckwith – was recovered within the hour in some nearby bushes. Eleven days after the assassination, Beckwith was arrested and charged with Evers’s murder. Tried twice by all-white juries, both cases ended in mistrial despite unmitigated evidence. Beckwith remained free for over thirty years until Evers’s widow finally forced the Mississippi courts to bring him to justice. In 1994, Byron De La Beckwith was sentenced to life in prison.

Myrlie Evers carried on her husband’s work, and became the first fulltime chairperson of the NAACP. She was also an influential campaigner for Barack Obama. When Obama was elected, Myrlie visited her husband’s grave at the Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia and told him: “We won.” Medgar Evers would no doubt agree that a black president represents a major victory, but he would also be all too aware of the work still to be done. He made the ultimate sacrifice for his cause. May the memory of Medgar Evers continue to endure and inspire new generations to finish what he started.

5 Responses to 12th June 1963 – the Assassination of Medgar Evers