The British Isles has a long history of invaders: Angles, Danes, Saxons, Vikings. But on 28th September 1066, when William, Duke of Normandy, landed at Pevensey in Sussex, an invasion force on this scale had not occurred since the Romans a thousand years before. William’s fleet of ships contained perhaps 8,000 men and hundreds of horses. He meant business.

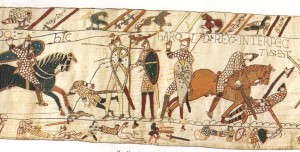

Two weeks later, on 14 October 1066, William and his army gathered at Senlac Hill, Hastings, and got into position to fight King Harold Godwinson’s English army. But Harold’s army was in a bad way. Depleted in number and war-weary from fighting the Norwegians in Yorkshire only weeks before, Harold’s infantry marched the 300 miles from the north so quickly that by the time they arrived on the south coast they were already knackered. Armed with battleaxes, swords and shields and dressed in chain mail, the English always fought on foot. The Normans were heavily armoured, carried swords, lances and the fiercely accurate crossbow and fought on horseback.

The battle was vicious with heavy losses on both sides. It wasn’t until William commanded his archers to fire over the English defensive shield wall to pick off the ranks at the back that the final blow was struck – so legend has it, an arrow in King Harold’s eye. William’s knights finished him off. The last Anglo-Saxon King of England was dead. Game over.

Having rested his troops, William marched on London. As he travelled towns he passed through submitted to him, as did towns farther afield to where William had sent messengers. On Christmas Day 1066 in Westminster Abbey, William the conqueror was crowned William the First of England. It was a seismic moment in English history.

Unlike most invaders before him, William intended to stay and colonise rather than loot and run. So he and the few thousand French nobles he’d brought with him had to devise cunning ways to control the land and the population of about 2 or 3 million.

The first thing to do was to confiscate all the land, evict English landowners and give it to his French cronies. But what, exactly, was out there? And so the Domesday Book, possibly the most detailed national statistical document in history, was commissioned. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states: “he sent men all over England to each shire to find out what or how much each landholder … and what it was worth.” It recorded everything: buildings, ownership, woodland, mills, wells, fisheries, abbeys, every ox and swine. He was now armed with facts.

But the English didn’t just roll over and take it lying down. In the first few years after Conquest, English lords resisted the hostile Gallic takeover. But it was hopeless. William’s men quelled uprisings with not just swords but also buildings. Oh, how William loved to build castles! Massive, highly visible and well-manned fortifications sprung up in many towns and cities – a clear sign to all who saw them: this is mine now, so shut yer festering gobs and fuck off. William adored churches too. The Norman Romanesque style of architecture, with round arches and strong columns was used in abbeys and monasteries, and in military architecture, too. The iconic Tower of London was built by William in the Norman style, and even constructed parts of it using French stone imported from Caen.

It wasn’t just the topographic landscape that had changed. The social landscape was turned upside-down. The Domesday Book shows that by 1086 King William personally owned 17% of the land in England, the Church 26% and 40% of the rest was held by just 10 men and 12 clergy, all of whom were French. To the English peasants at the bottom of the social pile, the conquest initially made little difference – whoever was lord of the manor, English or Norman, they still had to pay rent, pledge allegiance, grovel and scrape. Their new lord now simply spoke a different language.

Overnight, the Norman French language became the language of state, justice, the church and the hierarchy. We still use them: abbot, accuse, arch, baron, bigot, brigade, cavalry, chancellor, chattel, count, court, crime, defend, duke, evidence, jury, noble, parliament, plea, priest, prince, punish, revenue, royal, saint, tax, verdict, viscount: there are countless examples. It became the language of the kitchen too where we find:beef, boil, butcher, dine, fry, mutton, pork, poultry, roast and salmon, although for the live animal we preferred Old English ox, sheep and swine. Drinking wine, not beer, became de rigueur.

The English language was now seen as uncouth. But English, that most flexible of languages, quickly adopted new words. As Norman men forged alliances with English nobles, cementing them with marriages to local women, the infants of these unions would learn their mother’s tongue but with the addition of French loan words. Within a couple of generations, a new richness had been injected into the language. Whereas before in English we only had the word ‘motherhood’, we added the French ‘maternity’, a quite different meaning. Babies were given French names: Richard, Robert and William replaced Aelfric, Godfrith and Wystan.

The French invasion of 1066 is etched into English DNA. Despite attempts by subsequent forces to invade England by, for example, the Spanish Armada or Nazi Germany, our collective subconscious memory screams: never again! And indeed a foreign army has never since conquered our nation. But to our shame, we remember it selectively. The upheaval and change wrought by the Conquest is conveniently forgotten when we become the invading force. We justify it with words like liberator, civiliser (both words, incidentally, of Norman French origin). What shameful hypocrisy we have exhibited.

And yet we, tucked away in the top left hand corner of Europe on our little island, have always been invaded: by new ideas, new words, new peoples, races and cultures. And when we are wise enough to adopt these great new things, what a richer, more beautiful rainbow nation we become.

[Written by Jane Tomlinson]

2 Responses to 14th October 1066 – The Battle of Hastings and the Norman Conquest