Today is quite an anniversary for psychedelic culture. Exactly eight years ago the world lost one of its most remarkable visionary painters, the Peruvian Pablo Amaringo, whose art documented his shamanic ayahuasca visions. Forty-five years ago saw the death of the English spiritual rogue, Alan Watts, whose ontological subversions still carry weight today, cloaked with his charming wit. And seventy-two years ago marked the birth of Terence McKenna, whose untimely death in 2000 robbed us of a truly bardic champion of other dimensions.

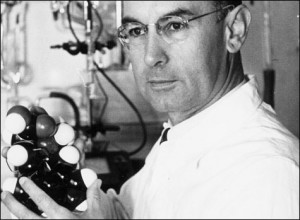

But none of these memorable events can hope to compete with an apparently innocuous November 16th in 1938 in the Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, Switzerland. For it was then that, searching for a respiratory or circulatory stimulant, Albert Hofmann stumbled upon a molecule whose effects on the world were to be wild and tricky, at once difficult to quantify and impossible to deny. Shelved for years, it wasn’t until “Bicycle Day”, April 19th 1943, that it was properly unleashed, as the genteel doctor took the compound for a test drive, and found himself on a startling, kaleidoscopic journey through the recesses of consciousness.

Initially the wondrous substance was restricted to an elite of health professionals investigating schizophrenia and treating alcoholism, intellectuals exploring consciousness, and artists expanding their sensual and conceptual horizons. But the evangelical zeal that LSD triggered in some, and its miniscule dosage levels, ensured that sooner rather than later, Hofmann’s elixir leaked onto the streets, and began dissolving, recombining and mutating the minds of individuals, and the cultural consciousness of our increasingly globalized human species.

What events, what dates following 16/11/38 would we pinpoint as crucial to the wider influence of LSD? The day in early 1961 when Timothy Leary, already pushing science’s boundaries with the Harvard Psilocybin Project, was blown away by the acid from Michael Hollingshead’s now-legendary mayonnaise jar? Perhaps we should pay heed to November 27th 1965, when Allen Ginsberg, Neal Cassady and The Warlocks (soon to be The Grateful Dead) joined a bunch of revellers near Santa Cruz for the first “Acid Test”? Or to January 14th 1967, when San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park was host to the “Human Be-In”, where the riotous social aesthetics of the Acid Tests exploded into popular consciousness, merging with Leary’s increasingly populist evangelism and the burgeoning array of civil and political movements of ’60s radicalism.

However, trying to nail the influence of LSD to particular dates is surely an exercise in futility. Just as the chemical’s interaction with your own consciousness will surely melt your reference points, tear you away from linearity, and force you to consider the sheer scope of the multi-levelled complexities that everyday life obscures, its permeation of Western culture in the final decades of the 20th century resists neat analysis. Hard political factions in the ’60s were of course suspicious of acid, because its corrosive effects on ideology were utterly non-partisan – though of course it has a certain affinity for ideas that promote selflessness and spontaneity. Perhaps for activism in tune with this mercurial catalyst, we might look to the San Francisco Diggers: community-minded, fiercely idealistic while retaining a sharp cynical edge, smart enough to see early on how “hippy” culture was mostly a distorting convenience for journalists, and free enough of ego to demand anonymity. Lee & Shlain, in their book Acid Dreams, relate that on one occasion “a journalist from the Saturday Evening Post dropped by the [Diggers’] Free Store and asked to speak with the manager. He was told that the manager was a shy person who didn’t like to answer questions but would make an exception in this instance. The man from the Post was then introduced to a Newsweek reporter who had been told the same thing. The two press stiffs questioned each other in a corner for twenty minutes before discovering that they’d been duped.”

But let us not forgot that however we try to define the impact of LSD on society, little of it would have been possible without the usually reluctant criminals who have made and distributed this chemical, which is heavily proscribed and demonized, yet routinely comes at the bottom of scales assessing the harm done by various drugs. Over two years ago, at a psychedelic conference in Basel, I saw the brilliant ethnobotanist Kathleen Harrison, who talked of her time among Mazatec Indians in Mexico. The shamans there are especially keen, when they haven’t grown or harvested their plant medicines themselves, to know the history of what is given to them. And whether we use something recreationally or spiritually, her advice for anyone relying on illicit channels – to at least pay heed to the journey of the substances we come by, and to offer thanks and prayers to anyone whose freedom had been risked or taken away for our benefit – seemed to be salutary. Anyone just in it for the money naturally deserves no attention. But rogue chemists such as Owsley Stanley and Tim Scully facilitated the influence of LSD as few others did. Until our culture can properly embrace discoveries such as that which occurred 80 years ago today, the real heroes of psychedelic culture will also be outlaws. Let’s salute those who have had years stolen from their lives in the name of repressing the freedoms of consciousness.

[Written by Gyrus]

Pingback: Journalists in “easily duped” shocker «