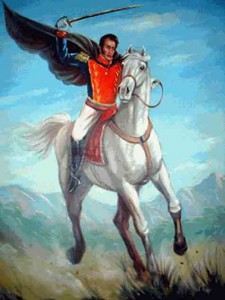

“I swear before you, I swear before the God of my fathers, I swear by my fathers, I swear by my honour, I swear by my country that I will not rest, body or soul, until I have broken the chains with which Spanish power oppresses us.” Thus declared Venezuelan-born Simon Bolívar at the age of 21. And, true to his word, the legendary Hispanic American revolutionary hero devoted his entire adult life to the liberation of millions of South Americans from tyrannical Spanish imperialism and oligarchy. Bolívar’s tireless efforts succeeded in emancipating all of the northern half of South America from colonial despotism and gave rise to the five independent nations of Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela and Bolivia – one of very few countries to name itself after an individual.

But while his military successes earned him the reverent title of El Libertador, Bolívar was also a visionary whose “Bolivarian dream” is widely recognised as an early precursor to the modern Pan-Americanism espoused over a century later by another great Latin American revolutionary, Che Guevara. At the peak of his post-liberation political powers, Bolívar attempted in 1826 to organise a league of Latin American states to promote solidarity and military cooperation among the developing nations, proposing the adoption of a constitution that would ease the nascent republics gradually toward democracy. The colonial legacy of three centuries would not, however, be eclipsed overnight – and the fragile South American union refused to ratify the constitution.

Bolívar’s greatest political mistake was his failure to recognise the raging forces of nationalism, which would erupt into civil wars and bitterly divide the union that he had so vociferously fought for. As a last desperate attempt to realise his grand plan, Bolívar betrayed his Rousseauian principles of political reform and proclaimed himself dictator. Dissent was immediate, and Bolívar’s popularity plummeted just as rapidly. There was even an assassination attempt on the once unassailable Libertador.

Bolívar resigned his presidency, and descended into a prolonged state of self-reproach. There was to be further humiliation when the new Congress of Venezuela refused to negotiate with Colombia as long as Bolívar remained on Colombian soil, followed swiftly by Ecuador’s declaration of independence from Colombia and finally armed revolt in Bogotá – all of which devastated Bolívar, who reluctantly made plans for exile in Europe. But shortly before his departure, he succumbed to suspected tuberculosis. Ten days before his death, he dictated his last will and testament to his people:

“You have witnessed my efforts to establish liberty where tyranny once reigned. I have laboured unselfishly, sacrificing my fortune and peace of mind. When I became convinced that you distrusted my motives, I resigned my command. My enemies have played upon credulity and destroyed what I hold most sacred … my reputation and my love of liberty. I have been the victim of my persecutors, who have brought me to the brink of the grave.”

And so it was that at the age of 47, Bolívar died hated by those whom he loved. But it was not long before his reputation was restored, and his fame across Latin America has continued to grow to mythical proportions ever since. Bolívar’s legacy is currently enjoying a renaissance in his beloved birth country of Venezuela, spearheaded by the recently deceased Hugo Chávez. In such hallowed esteem did President Chávez hold his ancestral soul-mate that he called his reforms a “Bolivarian Revolution”, renamed the country the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and left a chair empty at all political meetings in honour of El Libertador.

5 Responses to 17th December 1830 – the Death of Simon Bolivar