“If somebody kills themselves, they have the last word.” – Deborah Curtis

“If somebody kills themselves, they have the last word.” – Deborah Curtis

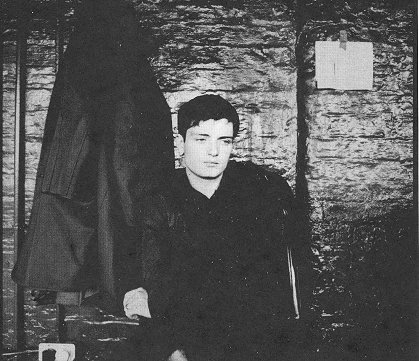

Thirty-eight years ago today, Ian Curtis killed himself.

Tragic rock’n’roll deaths, and suicides especially, are such obvious breeding grounds for romanticised cults. We’ve mythologized Cobain and Curtis to such an extent that it is impossible to consider their music separately from the heavy reality of what happened next. We’ve morbidly, voyeuristically, pored over the hideous clues in Ian Curtis’s lyrics; our endless fascination at times resembling a highbrow version of Peaches Geldof’s death and the ensuing media & public hysteria (lest we forget the whole “Ian Curtis died for you” malarkey that a Google search now attributes to Paul Morley in the NME, but my own memory says it was Dave McCulloch in Sounds). Yet in our wallowing, we risk overlooking what is at the heart of these myths: they would not endure and we would not be so moved if the art was not worthy.

Ian Curtis was a great poet. His melancholic (as opposed to melodramatic) lyrics are fine and true enough to withstand isolated, black-and-white scrutiny. But, in the grand tradition of lyric poetry – which has always been an oral art – his words demanded vocalisation. And it was with an Artaud-like completeness that the sound and vision conceived by Joy Division provided the apocalyptically bleak foundation for the haunted poetry. The result was both mesmeric and metaphysical. It was a brand new sound and, although Martin Hannett’s distinctive production will forever betray its true age on the corporeal plane, those of us who bought Unknown Pleasures in 1979 knew without the benefit of tragedy-informed hindsight that we were experiencing something Eternal.

2008’s Joy Division documentary and the previous year’s biopic Control – based on Deborah Curtis’s book Touching From A Distance (which, I’m embarrassed to admit, I initially and rashly mocked but did a volte-face after I actually read it; it is most excellent) – did much to both debunk and propagate The Ian Curtis Myth. We learned that he was once a happy Bowie fan; an easy-going guy who liked to go to the pub, hang out with his mates and actually had a sense of humour. And, with a youthfully foolish lack of foresight, it had been his idea to get married (Control however falsely portrays a spontaneous suggestion from Ian to start a family even though Deborah admits in her book that this had been her wish). But while great effort is made to provide evidence that he was ‘normal’ (ie. he did not emerge from the womb tortured), we also discovered the downright eerie story behind “She’s Lost Control” and Ian’s own subsequent and beyond coincidental epilepsy; the countless notebooks he kept from a very early age, spilling over with poetry and lyrics; the evolution of that dance; and, most intriguingly, the truth about his relationship with Annik Honore. Both films also help us better understand the cocktail of struggles that proved to be lethal: he might have been able to conquer his relationship traumas if his epilepsy had been properly medicated and had he lived in a time when mental health was better understood. As it was, the landscape of the early 1980s working-class north was in no way equipped to help a sombre poet whose relentless inner soundtrack was Throbbing Gristle’s “Weeping”.

On the evening of May 18th 1980, my friend Tim phoned to tell me that we would not in fact be going to see Joy Division in two days’ time at NYC’s Hurrah as we had been so eagerly anticipating. Four months later, along with my fellow RnR obsessive Patty, I would witness New Order’s first-ever US show (Maxwell’s, Hoboken, New Jersey; pre-Gillian, with the three JD survivors timidly, uncertainly, taking turns on lead vocals). We hung out with the guys for a while after the show. All perfectly nice and chatty, they were so unlike what I was expecting. But what on earth was I ‘expecting’? I was already completely in thrall to the Joy Division myth.

Tempting as it is to dismiss the cult of the Rock’n’Roll Suicide as nothing but an emo-like celebration of the macabre, the quixotic attraction is verily but an adjunct to that most time-honoured and archetypal artistic theme: death (the Romantics themselves would overly romanticise 17-year-old Thomas Chatterton). Ian Curtis ensured he would have the “last word” on his artistic legacy, for there really can be no separation from his final statement and the art (“Cold as the grave, has the infinity of a Gustave Doré hell” was Jon Savage’s appraisal of Joy Division’s music in his forward to Deborah Curtis’s book). Yet if we accept the idea of a ‘myth’ not as a falsehood but as a sacred narrative that can provide a broader insight into life, then the Ian Curtis/JD myth is justifiably compelling as evidence of humanity’s profound relationship to art and our artists, and our ability and/or need to be deeply touched, if only from a distance.

RIP Ian Curtis. Ian Curtis Forever.

Pingback: (Post)punkklassieker du jour: Love Will Tear Us Apart | Krapuul