On this day in 1850, pioneering feminist, Transcendentalist leader, freethinker and intellectual giant Margaret Fuller drowned tragically when an Italian cargo ship carrying her and her family struck a sandbar just fifty yards off the coast of New York’s Fire Island. For eight agonising hours, the crew and passengers had huddled together on the forecastle, waiting in vain to be rescued. So close were they to shore that they could see the beach scavengers carrying off the washed-up freight of the stricken brig. Most of the passengers managed to swim to safety. But as the gale-force winds and waves broke up what remained of the ship, in desperation Margaret Fuller passed her two-year-old son to a crew member. She watched as they both drowned before she and her husband were swept out to sea by a massive wave.

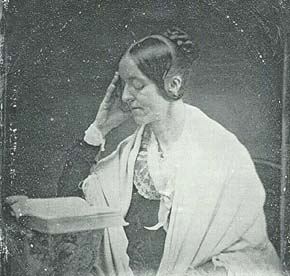

And so Margaret Fuller died as she had lived: extraordinarily, feverishly, inimitably. In her brief forty years, she’d been an author, editor, literary critic, educator, crusading journalist, foreign war correspondent, revolutionary, but most of all, a force. Her close friend Ralph Waldo Emerson considered her “the greatest woman of ancient or modern times.” Edgar Allan Poe declared, “Humanity is divided into men, women, and Margaret Fuller.” She possessed one of the most formidable minds of her era: a child prodigy, she was translating Virgil by the age of six; by thirty, she was considered the most well-read person – male or female – in all of intellectual New England. But in an age when medical experts warned that overstraining the mental faculties was so dangerous for women it could lead to premature death, Margaret Fuller faced overwhelming gender obstacles to realise her potential and ambitions. Denied the right to a higher education because of her sex, she had to make do with being the first woman allowed to conduct research in Harvard’s libraries. Shorn of the same avenues as her male colleagues of earning through lecturing, she enterprisingly conceived of “conversations” for Boston women. Fuller encouraged her audience to raise themselves out of their condition of dependence to one of self-reliance. To expand their intellectual horizons. These radical dialogues led Fuller to write her groundbreaking work, Woman in the Nineteenth Century – the first American feminist treatise that would have a profound influence on the approaching women’s movement.

We would have every arbitrary barrier thrown down. We would have every path laid open to woman as freely as to man … then and then only will mankind be ripe for this, when inward and outward freedom for woman as much as for man shall be acknowledged as a right, not yielded as a concession.

Such world-shattering ideas compelled Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton to declare that Fuller “possessed more influence on the thought of American women than any woman previous to her time.”

After presiding at the helm of the Transcendentalists’ landmark journal The Dial for four years, in 1844 Fuller was recruited by publisher Horace Greeley to join his New York Tribune as a literary critic. She went on to become the publication’s first female editor and first female foreign correspondent when in 1848 she was dispatched to Europe to cover the crises sweeping across the Continent. There she met and fell in love with an Italian revolutionary and disinherited marquis eleven years her junior, Giovanni Angelo Ossoli. Together they supported Giuseppe Mazzini’s 1849 revolution for the establishment of a Roman Republic – Fuller sending back stirring dispatches to the Tribune as well as volunteering at the front-line hospital. She and Ossoli had a son, did or perhaps didn’t get married, and Fuller wrote a book on the Italian rising before the destitute couple made the fateful decision to secure discounted passage back to America on a cargo ship so heavily laden with marble it was deemed unsafe by her friend Robert Browning. When the ship struck the Fire Island sandbar after two interminable months at sea, it began breaking up immediately due to its excess weight.

Margaret Fuller wrote America’s first major feminist work. She was her country’s first full-fledged female intellectual. But her life was blighted by a gender crisis that consumed her. “Tis an evil lot to have a man’s ambition and a woman’s heart,” she decried. What must it have been like for this brilliant woman to know with absolute certainty that there were few if any minds comparable to her own? But yet she was forced to suffer the limitations and discriminations of her gender in a male-dominated world that could not yet accept that women were capable of genius. Even though her once forgotten works have thankfully been reclaimed by modern women, the tragedy of her legacy is this: if Margaret Fuller had been a man, she would in life and death have been as renowned and esteemed as Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Pingback: Donne e giornalismo: la realtà del passato a confronto con quella di oggi | Soft Revolution