On New Year’s Day in 1804, Haiti proclaimed its independence: After ten years of struggle, an army of former slaves led by their charismatic leader Toussaint L’Ouverture had fought the French and British to a standstill. After the British colonies in North America, it was the first colony of a European power to win its freedom and establish a radical regime – the likes of which would not be seen again until the collapse of empires after the Second World War. Most significantly, slavery there was ended not by benevolent abolitionists but by the self-emancipation of slaves themselves. And despite the poverty and tragedy that has plagued Haiti in the past century, the ‘Black Jacobins’ remain an inspiration to all liberation movements.

Haiti was previously the French colony of Saint-Domingue – created in the 1690s when they seized the western half of the Spanish island colony of Hispaniola. In the eighteenth century it became the most profitable plantation economy in the world.

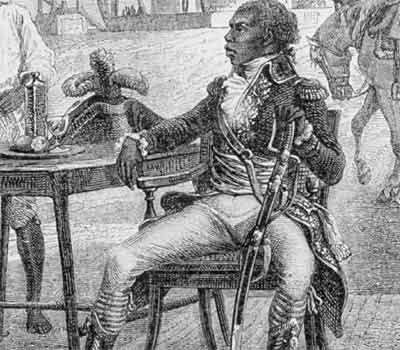

As in many other colonies there were frequent slave revolts – but also an emerging local elite based on a racial hierarchy with the white colonial merchants on top and an intermediate layer of ‘mulattoes’ of mixed-race. In an echo of the initial demands of white colonists in America, this group sought recognition and representation from France. The revolution of 1789 and the creation of a National Assembly raised these aspirations. The French colonial administration responded equivocally with a policy that gave some concessions – and included the mulattoes in an attempt to divide and rule. However this strategy did not work and thousands of slaves joined an uprising to press these demands. And it was at this time that Toussaint L’Ouverture – a former slave who had won his freedom to become a small-scale landowner – emerged as a leader. Although initially defeated, after taking advantage of the growing turmoil at home in France, by 1793 the slave army and their allies had seized control of the colony.

Understandably Toussaint L’Ouverture looked to the new radical Jacobin regime for support in abolishing slavery. In Britain, prime minister Pitt had previously been edging towards abolitionism, but fear of a domino wave of slave revolts and the prospect of incorporating the highly profitable French colony proved too tempting. The British sent an expeditionary force and restored slavery in the areas they controlled whilst the slave forces fought a guerrilla campaign, with some hesitant French support. But the end of Jacobin rule in 1795 and the installation of the reactionary Directory marked the end of any hope of support from France. In those areas controlled by L’Ouverture’s forces a radical regime was established that abolished slavery, reformed the justice system, introduced schools, and regulated working hours and conditions.

In a glimpse of the kind of post-colonial regimes that would emerge in the 1950s and 60s, L’Ouverture ruled as an enlightened autocrat dependent on military rule – although in contrast to later regimes he made no personal gains from the state he had built. However, with the formerly profitable colony now isolated and besieged by the western powers, poverty gripped the island. Discontent rose as L’Ouverture even resorted to forced-labour in an attempt to keep the economy going and in 1802 there was a rising against his rule. Although the rising was defeated, Napoleon at the head of a new stabilised and strengthened French regime co-operated with his enemies in Spain and Britain to crush the liberated areas and restore colonial rule. In the course of the campaign some 100,000 Haitians and 50,000 French were killed.

The prospect of fighting an on-going guerrilla war in conditions where sickness claimed as many casualties as battle would prove too much for the western powers. Like later imperialists, eventually France had to acknowledge that the war was unwinnable – but not before L’Ouverture had been tricked into giving himself up for negotiations and taken back to France where he would die in prison. It was left to his successor as commander of the slave army, Jean Jacques Dessalines, to formerly declare the independence of the world’s first ‘Black republic’.

The story of Haiti following independence has not been a happy one. In a sense the western powers never forgave its challenge to their power. France under the restored monarchy of Charles X sent an invasion force in 1825 in an unsuccessful attempt to restore colonial rule. Haiti later became the first country to have economic sanctions imposed by the United States, who in 1915 sent a military force that remained in occupation until 1937. Constantly blighted by poverty – which was consistently the worst in the whole of the Americas – Haiti was subject to a succession of autocratic and despotic regimes. Some of these, in the spirit of L’Ouverture, were benevolent and enjoyed varying degrees of popular support. Others were appalling in their repression, in particular the post-war regimes of the Duvalier dynasty. In an all too familiar pattern, these have at different times been supported, tolerated and occasionally brought into line by the western powers depending on the economic stability they provide, and the extent to which they provide a bulwark against revolution in the region.

As a footnote to this story, the definitive history of Toussaint L’Ouverture and the Black Jacobins is that of CLR James published in 1938. Few people can claim fame in both cricketing and revolutionary circles – but CLR James, the grandson of a former slave, came to England from Trinidad to become sports correspondent of The Guardian. Living amongst the mill workers of Lancashire he was drawn through their struggles towards Communism, rejected Stalinism and became part of a small group of early British Trotskyists.

[Written by journeyman]