“No theory, no ready-made system, no book that has ever been written will save the world. I cleave to no system. I am a true seeker.”

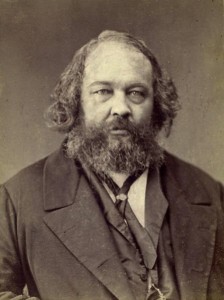

Today we contemplate the extraordinary life and legacy of Mikhail Bakunin, the revolutionary colossus and leading spirit of 19th-century anarchism who on this day in 1876 died in poverty and defeat at the age of sixty-two. Out-manoeuvred and out-cast from the First International by his ideological rival Karl Marx, Bakunin spent his final years licking his wounds in Bern, Switzerland – forced to rely on the benevolence of his followers, his health deteriorating rapidly after years of cigar smoking, brandy drinking and revolutionary struggle. It was an incongruously sober end for this rabble-rousing firebrand, famously described by a contemporary as a “man born not under an ordinary star, but under a comet.” A frontline revolutionary, Bakunin fought on the 1848-9 barricades in Paris, Prague and Dresden. He survived capture and incarceration in Saxon and Austrian prisons, two death sentences, a further eleven years of incarceration in his Russian homeland – including a long stint in the notorious dungeons of the Fortress Peter and Paul – culminating in Siberian exile, from whence he undertook a spectacular escape to western Europe via Japan and the United States. So busy was he living his revolutionary ideas that Bakunin left behind no great definitive tome containing them. Nevertheless, when he could muster it, he was a brilliant, incendiary writer. His most cohesive work – God and the State – remains a perennial in revolutionary theory, while his numerous pamphlets and essays provide insight into his ideas of collective anarchism:

The liberty of man consists solely in this, that he obeys the laws of nature because he has himself recognized them as such, and not because they have been imposed upon him externally by any foreign will whatsoever, human or divine, collective or individual.”

But while Bakunin is undoubtedly one of the key anarchist thinkers and activists of the 19th century, on this anniversary of his death, we remember him primarily as a prophet. A prophet whose visions extended clearly and far-sightedly enough to recognise that Marxism would only create in its leaders monstrous substitutes for those ‘divine figures’ who had for centuries ruled us before. Joseph Stalin. Mao Zedong. Pol Pot. Decades before they came to power, Bakunin predicted the inevitable rise of this new breed of tyrant when he wrote:

They [the Marxists] maintain that only a dictatorship — their dictatorship, of course — can create the will of the people, while our answer to this is: No dictatorship can have any other aim but that of self-perpetuation, and it can beget only slavery in the people tolerating it; freedom can be created only by freedom, that is, by a universal rebellion on the part of the people and free organization of the toiling masses from the bottom up.

For recognising and challenging this fundamental flaw, Marx conspired to expel Bakunin from his revolutionary steering group – the International Workingmen’s Association – engendering the red and black division of the anarchist flag. This marks one of the pivotal turning points in modern history. How different might the twentieth century have been had Marx but accepted and accommodated Bakunin’s prophecy? Thus, for all his brilliance, for all his flaws, Bakunin’s legacy must be defined by his objection to Marxism; the prophet who foresaw the authoritarian horrors lurking within such a seemingly sublime idea.

It’s a legacy that begets one of the greatest “what ifs” in history.

2 Responses to 1st July 1876 – the Death of Mikhail Bakunin