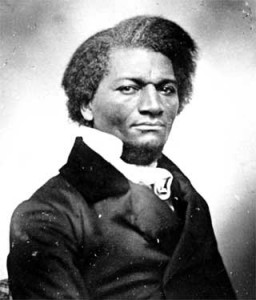

Today we pay tribute to a true colossus – the abolitionist, writer, orator and America’s first black leader of national stature, the inimitable Frederick Douglass. Born into slavery, separated in infancy from his mother and shunted from one pitiless Maryland plantation to another, Douglass never even knew what day or year he was born. But through luck, pluck and bona fide brilliance, Douglass would cast off the shackles of his slave roots to become one of the most important Americans – black or white – in the whole of the 19th century.

Following a daring escape to freedom at the age of twenty, Douglass published an account of his struggle that captivated the world and launched him as a public figure, great orator and star spokesman of the burgeoning abolitionist movement. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave recounted the horrors of human bondage in a prose so eloquent that many sceptics doubted such radiant talent could possibly have poured forth from a former slave. But the intelligentsia embraced this brilliantly written narrative that not only blew the whistle on American racism and its two-tiered structure of Freedom but, at its very fundament, challenged the ignorant notion that blacks had no intellectual aptitude. Douglass was the first African American to prove otherwise, achieving international fame as a writer of almost mystical genius and an orator with few peers. And, of greater significance, he provided an indomitable voice of hope for his people:

“Why am I a slave? Why are some people slaves, and others masters? Was there ever a time when this was not so? How did the relation commence? Once, however, engaged in the inquiry, I was not very long in finding out a solution to the matter. It was not color, but crime, not God, but man that afforded the true explanation of slavery; nor was I long in finding out another important truth, viz: what man can make, man can unmake.”

Frederick Douglass’ life intersected with some of the most momentous events in American history: the abolitionist movement, John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, the Civil War, Reconstruction, black suffrage and women’s emancipation. And, in a public career that spanned fifty years, Douglass’ actions and influence throughout such epochal times would be pivotal. In thousands of speeches and editorials, he levied an inarguable indictment against slavery and racism. He personally helped more than four hundred slaves reach freedom through the Underground Railroad. For 16 years, Douglass edited the most influential black newspaper of the mid-19th century. During the Civil War, he advised Abraham Lincoln and fought for the inclusion of black soldiers in the Union army which ultimately led to victory for the North. After the war, he crusaded for voting rights: “Slavery is not abolished,” Douglass said, “until the black man has the ballot.” Throughout Reconstruction, he unyieldingly pursued his commitment to civil rights for African Americans. And, for twenty years, he was at the forefront of the women’s suffrage movement. On the very day he died, he’d just returned home from speaking at the National Council of Women.

A symbol of his age, Frederick Douglass was a new and unique American voice for social justice. By demanding and daring to learn to read and write, he unearthed within himself a rare command of the English language that helped free millions of Americans. His incisive writings and electrifying lectures edified a doubtful American public far more directly and emotively than any white apologists could ever have hoped to match. Who but the wholly inhumane could not be shamed by the unflinching words in his now-famous 1852 speech, “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro”?:

“What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sound of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciation of tyrants brass fronted impudence; your shout of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanks-givings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of the United States, at this very hour.”

4 Responses to 20th February 1895 – the Death of Frederick Douglass