On this day in 1831, Nat Turner – a slave and lay preacher from Virginia – calmly explained to six of his fellow slaves that the moment had come for him not only to lead his people out of bondage, but to destroy its racist institution entirely. Over the next two days, Turner and his accomplices – over seventy in number at the rebellion’s peak – embarked on a policy of such rampage and unswerving butchery that fifty-five whites across Southampton County would be massacred in what was to become the largest slave revolt in US history. As the messianic Turner stated: “It was my object to carry terror and devastation wherever we went.”

Born in 1800, Turner had been taught to read by his first owner who believed literacy – or, specifically, being able to read the Bible – was necessary to the salvation of slaves. Turner learned quickly, displaying a formidable aptitude that surprised his master and awed the other slaves. He developed radical ideas on liberty and freedom from the Bible, and was soon preaching to the other slaves the concepts of self-respect, justice and resistance. His exceptional gifts convinced others he was a prophet (in addition to his intelligence, he had ‘markings’ on his body) – particularly after he started experiencing visions in 1825.

The visions revealed the specific mission Turner was to undertake; he believed that he was chosen by God to deliver his people from bondage and “slay my enemies with their own weapons.” He was told he would know the time to act when the signs were manifested, and the first sign duly came on 12th February 1831 in the form of a solar eclipse. And then on 13th August 1831, a green halo appeared around the sun. This was the final sign Turner had long been waiting for.

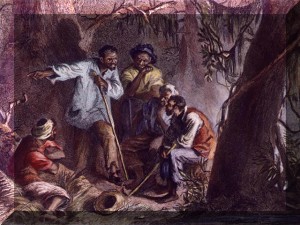

Eight days later, on the balmy evening of 21st August, Turner and six of his most dedicated disciples met in the woods for a quasi-religious ‘last supper’. While the others drank copious amounts of rum, teetotaler Turner set out their mission. The insurrection began in the early hours of 22nd August as the small band of seven rebels – armed with axes, knives and swords – butchered Turner’s owner, Joseph Travis, and his entire family in their beds as they slept. They then pressed on to neighbouring plantations where, in accordance with their plan, they recruited new helpers and killed any white person in their path: “Until we had armed and equipped ourselves, and gathered sufficient force, neither age nor sex was to be spared.”

The killing of whites was indiscriminate and savage, and there are accounts of torture and mutilation; moreover they cut the Achilles tendons of a slave who refused to join the rebellion. Most slaves in the area however were quick to follow the messianic Turner until, by 23rd August, the ranks of rebels numbered over sixty. At this point Turner decided to march on Jerusalem, the presciently named county seat of Southampton. However, news of the revolt had by then spread and the incensed white community mobilised in response to such an unthinkable outrage. A band of armed white militia was waiting for the slaves on the road to Jerusalem. As shots rang out, Turner’s group scattered.

By 25th August, after several attempts to regroup had failed, Turner went into hiding. For six weeks he managed to avoid capture but was finally discovered by a farmer named Benjamin Phipps. After surrendering without a fight, he was taken to prison on 30th October 1831 to await his inevitable fate. Meanwhile, the white community responded to the uprising with their own retribution. While thirty were tried and executed for their crimes, an estimated 150 slaves – most of whom had nothing to do with the revolt – were killed by vigilante mobs.

In the wake of the rebellion, southern fears of further slave uprisings led to several significant ramifications. As the culture of fear spread, many Virginians were suddenly concerned about the amount of slaves present in the state. A series of ‘slave debates’ occurred throughout 1831–1832 with many pushing for removal of slaves through colonisation outside of the United States, and abolition was even mooted. Instead, pro-slavery factions tightened control through legislation. Large groups of slaves were no longer allowed to gather together and literacy laws were passed throughout the South to quell religiosity; if they could not read, they could not read the Bible. But Nat Turner’s revolt also raised awareness and radicalised opponents of slavery. Twenty-eight years later, abolitionist John Brown would be inspired by and attempt to emulate Turner’s tactics – verily sparking the American Civil War.

Nat Turner was sentenced to execution on 11th November 1831. He was calm as he was led to an old oak tree northeast of Jerusalem, Virginia. And when the sheriff asked if he had anything to say before tying the rope around his neck, Turner replied: “I’m ready.”

7 Responses to 21st August 1831 – Nat Turner’s Rebellion