“I have never claimed that liberty will bring perfection, only that its results are vastly more preferable to those that follow authority.” – Benjamin Tucker

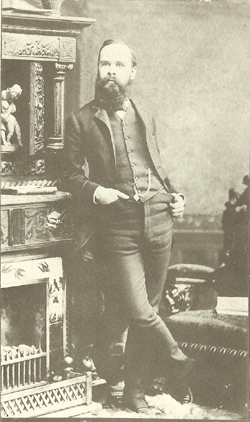

Not with any spectacular knock-out blow did today’s subject achieve his legacy in the pantheon of American anarchist luminaries. He wasn’t a “propaganda-by-the-deed” anti-hero like Alexander Berkman; nor was he an inspiring, fiery, superstar orator like Emma Goldman. Despite being a brilliant and original thinker with a great gift of literary craftsmanship, he left behind no defining opus. Instead, Benjamin Tucker earned his place in radical history as a Pied Piper of anti-authoritarian thought through a sustained and dedicated life-marathon.

As a radical publisher and accomplished translator, he was instrumental in introducing the ideas of Proudhon, Bakunin, Stirner, Hugo and Tolstoy to America. As a first-class journalist and the first American – indeed, the first Anglo-Saxon – to start an avowedly anarchist newspaper, Tucker did “more practical work for the advancement of liberty than any other man, living or dead.” This exalted accolade (from fellow anarchist, Laurance Labadie) recognised that Tucker – as the chief voice of the world’s dominant anarchist journal – held extensive influence over the movement during its most influential years. Founded by Tucker in 1881, Liberty was a milestone in the history of anarchism. For thirty years, Tucker published, designed, edited and wrote for this paper that aspired to “contribute to the solution of the social problems by carrying to a logical conclusion the battle against authority.” In doing so, it touched on every social question of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, carried translations and articles from the seminal radical thinkers of the era and sparked anarchist movements around the world.

As to be expected of such a prominent 19th century radical, Tucker’s life was not without controversy or drama – not least being seduced at the age of 18 by leading suffragist and free-love advocate, Victoria Woodhull, sixteen years his senior. But it is as the Publicist of Anarchism for which we today pay tribute to Benjamin Tucker. He was a man of ideas who nevertheless understood the enormous value of facilitating and spreading the ideas of others, and he served his cause with responsibility, steadfast conviction, uncompromising idealism, literary finesse and a mightily impressive altruism.