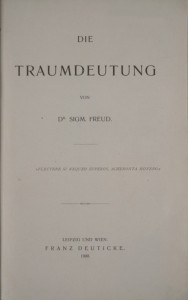

Today we’re stepping back to the Autumn of 1899. To the day when a small academic printing-press in Vienna produced two advance copies of a book that was to herald a cultural revolution. A book that initially struggled to find a wide audience – the first print-run was 600 copies and it was almost a decade before a second was required. But a book, nonetheless, whose influence on modern humanity has few parallels. Certainly you could make a decent case for including it alongside the likes of The Communist Manifesto or On the Origin of Species among the handful of books that helped define modern culture.

Of those two original copies of Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams, one remained with the author while the other was mailed to his friend Wilhelm Fliess for comment and feedback. Six months later, in a letter to Fliess, Freud would write, “not a leaf has stirred to reveal that The Interpretation of Dreams has had any impact on anyone”. I imagine him writing that letter and pausing to stare forlornly at a big box of unsold books in the corner of the room. Blissfully ignorant of the approaching storm.

And a storm it was. It wasn’t long since Nietzsche had announced the death of God, and it was only five years until Einstein would publish Relativity and the 20th Century could get underway in earnest. Rarely has the human experience changed so rapidly. It was the Renaissance, but industrialised. Versailles, Joyce and cyberspace were on their way. And in the midst of all this exploded The Interpretation of Dreams, the foundation stone of psychoanalysis.

Back then Freud believed he was building a new science. A discipline that would do for the mind what medicine did for the body. And not just in the sense of “healing”, but just as importantly, “understanding”. He came from a medical background and took a strict biological view of the mind. It was clearly a product of the body, he felt, and he had no doubt that as we better understood neurochemistry, so we would better understand the mind. But at the same time he understood that as a phenomenon the mind merited at least as much study as the body that produced it – not least because that phenomenon seemed to be the very thing we meant when we used the word, “I”.

Neurobiology now tells us that as memories are formed, so protein clusters in our parahippocampal gyrus get reconfigured. Almost like the grooves on a record. And as important and interesting as that information is, it tells me nothing about why the smell of jasmine makes me feel nostalgic and the sound of John Lennon’s voice makes me happy. Many would say we shouldn’t be poking the scientific method into such things, but for better or worse, that’s what Freud did and in so doing he ushered in what Adam Curtis called The Century of The Self.

It wasn’t long before Freud himself would question the wisdom of unleashing his ideas upon the world. With the publication of the second edition of The Interpretation of Dreams in 1909, he was persuaded to give a series of lectures in the United States. As the ship pulled into port and Freud saw the small welcoming committee of academics, all smiling happily, he whispered to his travelling companion, Carl Jung, “they don’t realise we are bringing them The Plague”. Later he watched with anger and alarm as his nephew Edward Bernays expropriated his theories and methodology and used them to shape the emerging public relations industry and the ideology of consumerism it promoted.

Because far from being just another book about dreams; of which there were many published around that time; The Interpretation of Dreams held an entirely new language within its pages. It would frame the way we spoke about the mind, about the very experience of being human, for the next century and beyond. And despite the current disdain for psychoanalytic theory in modern mainstream psychology, that first Freudian map of the mind, published in October 1899, retains a powerful grip on our imagination.

For while Freud’s place in modern culture might appear, above all, to be as a punch-line for jokes; appearances can be deceptive. The list of influential artists of the 20th century who were themselves influenced by Freud (and by the reactions he provoked) is simply too long to even choose a representative sample. Film and television, literature, painting, sculpture, song-writing – Freud’s presence can be found wherever you look. Philosophy, particularly the philosophy of mind, has never been the same since (or “has never recovered” as some might phrase it). The very fabric of our culture; consumerism and the wall of mass media advertising that drives it; political propaganda; right down to the way we think and talk about mythology, family, sexuality, personality… ourselves; all incorporate Freudian ideas to a greater or lesser degree.

Later in his career, he seemed to realise that his attempt to build a “hard science of the mind” could never succeed, that the unconscious couldn’t be poked and prodded like the parahippocampal gyrus. But to Freud that wasn’t a sign that our investigations into it should cease, merely that we required a different approach. As he himself acknowledged:

“Everybody thinks that I stand by the scientific character of my work and that my principal scope lies in curing mental maladies. This is a terrible error that has prevailed for years and that I have been unable to set right. I am a scientist by necessity, and not by vocation. I am really by nature an artist… And of this there lies an irrefutable proof: which is that in all countries into which psychoanalysis has penetrated it has been better understood and applied by writers and artists than by doctors. My books, in fact, more resemble works of imagination than treatises on pathology… I have been able to win my destiny in an indirect way, and have attained my dream: to remain a man of letters, though still in appearance a doctor.” — Sigmund Freud.

The Interpretation of Dreams was one of the books that Freud regularly updated throughout his life, with each subsequent edition containing revisions and sometimes substantial rewrites, leading to the confusing situation where a book first published in 1899 makes plentiful reference to books written years later. But by and large it’s not a confusing book. So steeped are we in Freud’s thinking, that reading it today feels strangely familiar and sometimes even, well, obvious. So it’s difficult to imagine just how controversial, radical, subversive… how genuinely revolutionary it was when it first found an audience.

[Written by Jim Bliss]

3 Responses to 22nd October 1899 – Sigmund Freud publishes “The Interpretation of Dreams”