On this day in 1976, power was seized in a coup d’etat by a military junta that would rule Argentina between 1976 and 1983. Throughout those seven grueling years, Argentines endured a repressive regime of indiscriminate violence, persecution, torture, kidnappings, theft of babies born in captivity, and – infamously – the disappearance and assumed deaths of an estimated 30,000 people. This unchecked state terrorism came to be known as the “Dirty War”.

The roots of the Dirty War go back to 1955 and the overthrow of the legendary populist President Juan Perón, heralding an unstable political period alternating between dictatorships and restricted democracies. The next 18 years saw Argentina plagued by antagonistic political sides – some linked to transformation by democratic means, others backing the military and those with economic power. In the first half of the ’70s the predictable became inevitable: a huge conflict and irreconcilable division between the two. This inauspiciously coincided with the 1973 American-backed coup in Chile against socialist president Salvador Allende. That same year, Perón returned to Argentina from exile and was rapturously received. He won his third term as president but had become so out of touch that he was unable to lead a country that had moved on in his absence. He died in 1974, leaving power to his third wife and widow Isabel – whose weakness opened the door for the seizure of power.

And so occurred the military coup on March 24th 1976 led by right-wing militant General Jorge Videla and his resultant “Process of National Reorganization”: a conservative, militarized, Catholic vision of what the country should be. But the truth of his vision included a campaign of extermination against the so-called “subversion” – a term that included intellectuals and militants of the left, freethinkers, atheists, homosexuals, disobedients, and other arbitrary ‘outcasts’. This Dirty War was part of the greater Operation Cóndor – an unholy alliance of intelligence and coordination between the military regimes of Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Brazil, Paraguay and Bolivia with connections to Peru, Ecuador, Colombia and Venezuela – aided and abetted by the United States through the CIA. The technical services of the CIA provided torture equipment and advised on how to deal “effectively” with resistance. US involvement along with the cover-up of crimes was a conscious policy proposed by Henry Kissinger who, according to Christopher Hitchens, was the ideologist behind Operation Cóndor. America’s involvement was only disclosed when secret documents were declassified during the administration of President Bill Clinton.

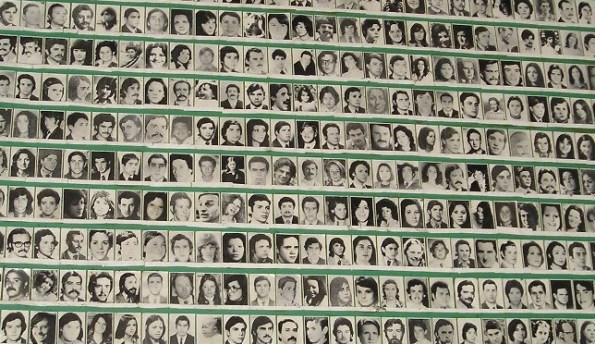

But while Operation Cóndor extended throughout South America, the Dirty War was Argentina’s own – the most macabre face of which was “los desaparecidos” or “the disappeared.” Many people, both opponents of the government as well as innocent people, “disappeared” in the middle of the night – taken to secret government detention centers where they were tortured and eventually killed. The Mothers of Plaza de Mayo deserve distinguished mention for their courage during these dark years. Demanding the whereabouts of their sons and daughters, they never stopped marching every Thursday around the pyramid of Plaza de Mayo opposite the House of Government wearing a white scarf on their heads made with cloth diapers to represent their lost children. Their struggle turned into a fundamental part of this bleak chapter in Argentina’s history: while the world turned a blind eye, they made the invisible visible. Some time ago one mother said ‘… not only was it a question of transmitting the truth, but also of finding it.’

The legacies of the Dirty War are many and Argentina has had to deal with them in different ways. In economic terms the consequences left the burden of an increased national debt as well as social inequality that continues to this day. As for the countless atrocities committed, these have been the subject of much discussion… but finally the issue of state terrorism and violation of human rights has begun to be addressed and redressed. There have been trials and convictions for many and that has served as balm for the survivors, but lest we forget that dictatorship is a past that remains present within the political agenda and some who are in power today once swam dangerously close to those sinister waters.

24 March is now a public holiday in Argentina – The Day of Remembrance for Truth and Justice – commemorating the victims of the Dirty War. And today in Argentina the story is quite another; better, although still uncertain. The precarious democracies of Latin America – mostly autocracies – are adept to the cult of personality: whoever yells the loudest tends to prevail. But the truth is that they don’t care about the people. Moreover, the temptation of rulers to succumb to corruption remains and looks like a perennial calamity in the form of tragic destiny.

[Written by Daniel Renne]