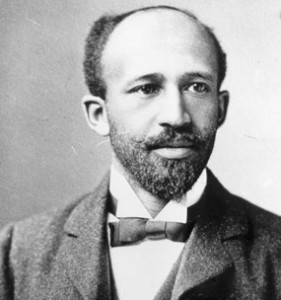

Today we recall the long, eventful and totally full-on life of W.E.B. Du Bois, the foremost champion of equal rights for blacks in the United States during the first half of the twentieth century, who died on this day in 1963 aged 95. During a time when many black Americans believed the only way to improve their social status was by assimilation and toleration of the dominant white society’s racist rulebook, Du Bois was instead a tireless advocate of unconditional equal and civil rights. Viewed merely as a scholar, educator, author and sociologist, Du Bois was a pioneering raiser of Black Consciousness. But as a civil rights leader and co-founder of the groundbreaking Niagara Movement and the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), Du Bois was nothing less than a harbinger of what would become Afro-Americanism. Being so forward thinking in his then-radical notions, Du Bois unfortunately would not live to see the adoption of his uncompromising ideas – choosing instead to die in self-imposed exile in Ghana, literally on the eve of a new era for the civil rights movement. But upon his death, the NAACP proclaimed him “the prime inspirer, philosopher and father of the Negro protest movement.”

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born on February 23, 1868 in Great Barrington, Massachusetts and became the first of his poor black family to graduate from high school in 1884. His local community was so impressed by his academic brilliance that they raised money in order to send him to Fisk University in Tennessee, where for the first time Du Bois experienced southern America’s deep-rooted hatred for blacks and its associated discrimination and segregation. He returned to the north to continue his education at Harvard, where he was the first black to receive a Ph.D. In 1898, he became a professor of history and economics at Atlanta University and it was during this time that Du Bois began to develop a social and historical documentation of blacks in the United States which, through his prolific and eloquent writings, serves as the greatest testimony to his ideas and impact.

Du Bois’ most significant literary contribution was The Souls of Black Folk wherein, for the first time, the peculiar “double-consciousness” of being both black and American was addressed in this series of essays that restored neglected black voices from the days of slavery and considered the “negro problem” as it existed in the Reconstruction era immediately after the Civil War. Published in 1903, The Souls of Black Folk appeared at a time when Social Darwinism – white culture’s alleged scientific justification for the policies of racial hatred and discrimination – had reached its apex and the Ku Klux Klan’s vigilante violence was on the assent: by 1899, one black person was being lynched every other day in the United States. In the introduction to the 1969 edition, Dr. Alvin F. Poussaint wrote: “Du Bois genuinely believed that if he could utilize his training in gathering and presenting the facts concerning the misery of the black man in America, those facts, indisputable in their logic and clarity, would move the white man to right the wrongs now made visible to him.” But Du Bois’ hope that education was the key to racial equality was shattered by the alarming increase of violent racism in the early twentieth century, and he thereafter concluded that change could only be achieved through direct black agitation and protest. He would devote the rest of his life to that cause.

In 1905, Du Bois founded the Niagara Movement, the first black organisation to insist on unconditional racial equality. The movement attacked the philosophy of the most influential black leader of the period, Booker T. Washington, arguing that Washington’s accommodationist policies perpetuated racism. The Niagara Movement collapsed after five years of internal conflicts and financial difficulties, many of which were alleged to have been the result of Booker T. Washington’s sabotage. Assessing the failures of The Niagara Movement, Du Bois concluded that an organisation which included the support of prominent whites was – after all – essential to the success of his mission.

In 1910, therefore, he compromised his militancy by co-founding the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which aimed to fight discrimination through court litigation, political lobbying and nationwide publicity. Ironically, Du Bois was the sole black director of this interracial organisation and he was often in ideological opposition to his co-directors. He nevertheless felt a moral responsibility to his position in the NAACP, particularly as editor of its journal, The Crisis, which provided a groundbreaking and influential platform for the discussions of America’s racial issues. By the 1930s, however, the NAACP had become more institutional and Du Bois more radical. He resigned, and dedicated the next two decades to his vision of Pan-Africanism and self-government for oppressed black nations. In 1961, having become increasingly alienated from and frustrated by the mainstream civil rights movement, Du Bois – a longstanding socialist – joined the Communist Party and declared in a public statement: “I have been long and slow in coming to this conclusion, but at last my mind is settled … Capitalism cannot reform itself; it is doomed to self-destruction. No universal selfishness can bring social good to all.”

Soon afterwards, having lost all hope that blacks would ever know freedom in America, Du Bois moved to the West African country of Ghana where he died on 27th August 1963. He received a state funeral and was buried on the grounds of the Government House. The very next day, nearly 300,000 people gathered in America for the “March on Washington” – the largest-ever civil rights demonstration that ended with Martin Luther King Jr’s momentous “I Have a Dream” speech. The civil rights movement had finally caught up with what W.E.B. Du Bois had predicted nearly sixty years earlier: that blacks could not remain submissive to a white society that would never voluntarily grant them equal rights.

5 Responses to 27th August 1963 – the Death of W.E.B. Du Bois