Today we lament the brutal suppression of the Kwangju Democratisation Movement. Ten days earlier, the citizens of the liberal South Korean city of Kwangju joined a student-led uprising in opposition to the illegitimate authoritarian rule of General Chun Doo-hwan. In response, Chun’s Special Warfare Command Troops beat, bayoneted and shot their way through Kwangju in an orgy of violence. Before it ended with the storming of the provincial capital in the heart of the city, hundreds were dead. Some human rights groups say the death toll was as high as 2,000. The United States failed to intervene, despite the fact that it maintained operational control over South Korea. The Kwangju Massacre represents a crucial turning point in modern Korean history, galvanising radicalism and anti-Americanism among a generation of youth, and heralding a new democratic movement.

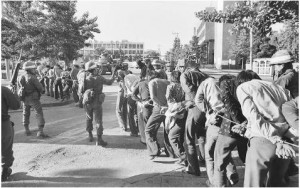

Chun Doo-hwan’s reign of power was dodgy from the get-go. He’d staged a barely successful coup at the end of 1979 – but when he moved to cement his illegitimate grip by declaring martial law on May 17th 1980, protests erupted all over the country. Most demonstrators were met with the tear gas and truncheons of the ordinary riot police. But for the students at Kwangju’s Chonnam National University, Chun Doo Hwan sent in his most brutal, American-trained special forces. The commandos burst in to the university, shot the ringleaders then rampaged around the town for a week beating or killing anyone who looked vaguely radical, or those who simply got in the way: children, pregnant women, Red Cross volunteers. Shocked by the frenzied brutality, the student demonstrations escalated into a full-scale uprising. Citizens armed themselves with weapons from police stations deserted by officers unable to stand against the army and unwilling to turn against the townspeople.

The “Kwangju liberation period” began on May 21st, when the army withdrew to the outskirts in the face of the furious citizenry. The Citizens’ Settlement Committee and the Students’ Settlement Committee were formed. Not since the days of the Paris Commune had a city claimed autonomous rule. But at 4am on May 27th, massively reinforced martial law troops with tanks and machine guns stormed the city. The civil militias were gunned down and defeated in just over an hour.

The short-lived Kwangju Democratisation Movement was founded on the principle of defending democracy from military usurpation. Chun, however, defended the massacre on the entirely false grounds that the demonstrators were armed communists trying to destabilise the country in anticipation of a North Korean invasion. He also accused well-known local dissident Kim Dae Jung of organising the uprising, even though Kim was in prison at the time.

The US government, meanwhile, said it was shocked and disturbed by Chun’s coup, his declaration of martial law and the Kwangju Massacre. But there were no economic or military sanctions, nor any kind of outcry. Instead, a mere two weeks after the Kwangju massacre, the Carter Administration assured Chun of continued financial support. Less than a year later, Chun was the first head-of-state invited to the White House by the newly elected president Ronald Reagan. What explanation could there be for brown-nosing such a turd? Under an agreement signed in 1953 after the Korean War, all forces in the South fell under American command. Verily, the United States was technically responsible for what happened in Kwangju. “American colonizers are behind all oppression in Korea,” asserted South Korean student leader Song Kap Suk, a speaker at the massacre’s 10th-anniversary memorial service, to rousing applause.

When democracy finally came to South Korea in the late 1980s, Chun was put on trial and convicted of mutiny and treason for the 1979 coup that brought him to power, and for instigating the Kwangju Massacre. He was sentenced to death, later commuted to life imprisonment. His henchman and successor, Roh Tae Woom, was sentenced to 22.5 years. Both were later pardoned. The protesters who died in the uprising were all declared martyrs for democracy, and the South Korean government has paid compensation to more than 4,000 who suffered injuries. Kim Dae Jung, the dissident whose arrest touched off the uprising, was elected president in 1997 and won the Nobel Peace Prize a few years later for his efforts to end the divisions between North and South Korea.

And America has swept the entire incident under its imperialistic carpet.

7 Responses to 27th May 1980 – the Kwangju Massacre