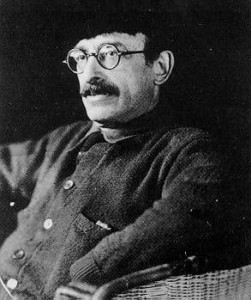

On this day in 1936, Alexander Berkman died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the chest. Suffering from poor health and broken dreams, it was a sad and discomfiting end to the noble life of this seemingly inexorable revolutionary who, together with one-time lover and lifelong companion Emma Goldman, had been the leading figure of the American anarchist movement at its early-twentieth-century peak.

A gifted writer, Berkman served as editor of Goldman’s hugely influential periodical Mother Earth, published his own journal, The Blast, and authored several seminal political works – his ABC of Anarchism remains one of the most concise and lucid explanations of anarchist philosophy. His writings endure as testimonials of one of the most pivotal political and social eras as well as blueprints for today and tomorrow.

But it is for one extraordinary act that the then 22-year-old Russian-born anarchist earned his place in historical infamy. Like John Brown before him, Berkman was ready to go to the furthest extreme on behalf of his cause. At the height of America’s labour struggles, he attempted to kill industrialist Henry Clay Frick in revenge for orchestrating the violent suppression of the Homestead Strike resulting in the death of seven steelworkers.

Berkman imagined that to assassinate a tyrant such as Frick would awaken the consciousness of the working class, identify for them the enemy, and startle the masses out of their lethargy. The fateful deed, Berkman prophesised, would ignite the revolution – and he was fully prepared to sacrifice himself in order to light the flame. But the plan backfired spectacularly. Not only did Berkman bungle the assassination, but the very people for whom he had intended to martyr himself were utterly disgusted by his act. They didn’t want revolution. They didn’t want freedom from tyranny. All they wanted was a few more crumbs. The Homestead strikers were all too quick to disassociate themselves from the “crazed Russian immigrant”, and even sent condolence messages to Frick, praying for his speedy recovery.

Berkman, meanwhile, was sentenced to twenty-two years behind bars in the severe Western Penitentiary of Pennsylvania. There, he wrote one of the great works of prison literature, Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist, wherein he offers not only an explanation for his act – but also a stirring justification for the controversial theory of propaganda of the deed:

Human life is, indeed, sacred and inviolate. But the killing of a tyrant, of an enemy of the People, is in no way to be considered as the taking of a life… True, the Cause often calls upon the revolutionist to commit an unpleasant act; but it is the test of the true revolutionist—nay, more, his pride—to sacrifice all merely human feeling at the call of the People’s cause.

Could anything be nobler than to die for a grand, a sublime Cause? Why, the very life of a true revolutionist has no other purpose, no significance whatever, save to sacrifice it on the altar of the beloved People. And what could be higher in life than to be a true revolutionist? A being who has neither personal interests nor desires above the necessities of the Cause; one who has emancipated himself from being merely human, and has risen above that, even to the height of conviction which excludes all doubt, all regret; in short, one who in the very inmost of his soul feels himself revolutionist first, human afterwards.

After serving fourteen years behind bars, Berkman was released and reunited with Goldman, threw his efforts into Mother Earth, helped found the Ferrer Centre in New York City and led the charge against conscription at the outbreak of World War One. For that he was once again imprisoned and eventually deported to Russia, where he witnessed the early days of State Bolshevism. He confronted Lenin and Trotsky, unsuccessfully tried to mediate in the Kronstadt uprising, and finally left the country deeply disillusioned. His subsequent account, The Bolshevik Myth, was one of the first to expose Soviet totalitarianism.

He spent his final years in poverty as an exile in France, dispirited by humanity’s failure to emancipate itself when it might at long last have had the chance to do so in the social revolutions of the early twentieth century.

As a man and revolutionary, Alexander Berkman was much, much more than he who shot Frick. He was one of anarchism’s greatest proponents, possessed of uncompromising integrity, altruistic idealism and without the power-hungry duplicity which tainted so many of his peers. He suffered imprisonment, torture, harassment, deportation and statelessness in the name of his convictions. But, to the end, he maintained that anarchism was “the very finest thing that humanity has ever thought of” – and never once expressed regret for his attempt on Henry Clay Frick. Throughout his long revolutionary career until his suicide at the age of 65, he at all times walked it like he talked it.

As the playwright Eugene O’Neill said to Berkman in 1927:

“As for my fame (God help us!) and your infame, I would be willing to exchange a good deal of mine for a bit of yours. It is not hard to write what one feels as truth. It is damned hard to live it.”

One Response to 28th June 1936 – the Death of Alexander Berkman