Today we lament the unfathomably brutal suppression of the first proletarian revolution in history, the Paris Commune. Just three months earlier, on 18th March 1871, the workers of Paris rose up, seized power from the new provisional French government, declared themselves autonomous and set about trying to reinvent society. The National Guard, recruited from all able-bodied men, replaced the police and the regular army. The separation of church and state was decreed. All church property was made public. Improved workers’ rights and education reforms were implemented. Interests on debts were abolished. And women were to be granted equal rights. In the absence of envy and oppression, a new kind of egalitarian social order emerged. “Paris is a true paradise!” the painter Courbet enthused. “No nonsense, no exaction of any kind, no arguments! Everything in Paris rolls along like clockwork. If only it could stay like this forever. In short, it is a beautiful dream!”

But the beautiful dream was about to implode, for the Communards had made a fatal error. In their idealism and magnanimity, the revolutionaries had failed to comprehensively overthrow Adolphe Thiers’ provisional government while its army was weak and demoralised following the humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. Instead, Thiers and his bourgeois government regrouped in Versailles and plotted with their former bitter enemy, the Prussians, to destroy the Commune.

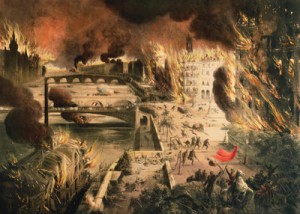

On 21st May at 2pm, in the prosperous western area of Paris, a Versailles officer noticed a white handkerchief being waved by a middle-class traitor near the Point-du-Jour gate. The government’s army was able to enter the fortified city through an opened gate; by nightfall, over 60,000 troops were inside Paris. There was no second line of defence and, despite an attempt to quickly erect barricades, the recent addition of boulevards made the inner city impossible to defend. The Commune was doomed.

And so the slaughter began. The massacres were indiscriminate; no one was spared, as to merely be Parisian was considered an act of treason. The barricades fell quickly and, each time they did, the defenders were put up against a wall and summarily executed. 300 were cornered and gunned down after they fled into the Madeleine church. When the Versailles troops captured the seminary at Saint-Sulpice, which had been turned into a hospital by the Commune, they executed all the medical staff and patients. The dead were left everywhere – the world-famous fountain in the Luxembourg Gardens overflowed with corpses. Word had reached Versailles of the strong feminist movement within the Commune, and a cynical rumour spread amongst Thiers’ troops of the pétroleuses, or “women incendiaries”, who were allegedly setting fires to buildings. Thus there was no mercy for women, who were savagely bayoneted in the streets. For eight days, the killing continued. Every Parisian pavement was a battlefield, every house a fort. On 28th May, the Communards were driven to a last stand at Père Lachaise cemetery. Thousands were herded together and shot. A part of “The Wall of the Communards” still stands; the sculptured faces at once a challenge to capitalist rule and a monument to the martyrs of the Commune.

Over 30,000 were killed in the week known as La Semaine Sanglante (“The Bloody Week”) – more than in the French Revolution. Up to 50,000 were arrested and imprisoned; some 4,000 deported for life to New Caledonia. It would take France decades to recover from the humiliation of the massacre. For Europe’s socialist movement, however, the Paris Commune was the ideal testing ground for revolutionary theory. Karl Marx hailed it as “the glorious harbinger of a new society” – evidence that a proletarian uprising could topple the bourgeois bureaucratic machine. He did, however, criticise the Commune for failing to launch an immediate attack on Versailles and for its failure to seize the gold reserves of the Bank of France. Marx accordingly revised his theory of the State, concluding that the working class had to smash the state – rather than take it over or leave it intact – and that to do so required a “Dictatorship of the Proletariat.”

But no one would better learn from the mistakes of the Commune martyrs than Vladimir Lenin: if the ruling class would show no mercy, neither could the working class.

10 Responses to 28th May 1871 – Defeat of the Paris Commune