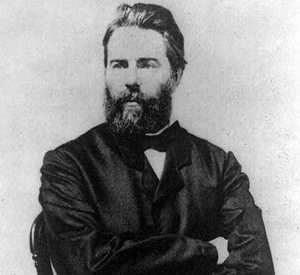

Today we pay tribute to Herman Melville, who died on this day 1891. At the time of his death at the age of 72, the author of Moby-Dick had abandoned his professional literary ambitions some twenty-five years previously; a victim of his own inanition and public neglect, he had subsequently fallen into such obscurity that a New York Times tribute remembered him as “The Late Hiram Melville”. He was subsequently ignored until the 1920s, when his genius was finally recognised and he took his rightful position as one of the great American writers. But rather than bemoan such unfortunate neglect in his lifetime, let us instead celebrate the events which led to Melville’s masterpiece. For not only would he sail the Pacific, survive fierce storms and jump ship to live amongst the “noble savages” of the South Seas – but, in the wake of a brief but incendiary literary friendship, he would also undertake a personal transformation so heroic and exceptional that we can only forgive the readers of 1851 for failing to recognise the brilliance of the work it inspired.

Herman Melville was 21 years old when he signed on as a sailor aboard the whaler Acushnet bound for the Pacific Ocean. His fantastic adventures for the next three years sparked a run of hugely successful autobiographical novels, including Typee and Omoo. In 1847, Melville settled down and married, and his trajectory as a popular author seemed assured until – on August 5th 1850 – he met the author, Nathaniel Hawthorne. Melville already knew about Hawthorne, but the appearance of The Scarlet Letter that same summer was a momentous event, proving that an American writer could create serious literary art to rival any European classic. An immediate and intense personal intimacy developed between them, and their relationship was to have a profound impact on Melville. Hawthorne’s metier of dark romanticism combined with the philosophical stirrings of American Transcendentalism was to awaken in Melville a new and urgent voice – and he set about the arduous task of completely re-writing and transforming a nearly completed book about a whale into something far greater than the typical sea-faring yarn by which he’d made his name.

A brave, vivid and allegorical exploration of humanity, Moby-Dick proved to be unlike anything Melville had ever written. And, upon its publication in 1851, it was a complete and utter failure. Melville’s readers, accustomed as they were to exotic page-turners, rejected the ambiguity that would one day see students and scholars finding hidden meaning and mystery within every passage. Melville’s subsequent novels yielded even less success; by the outbreak of the American Civil War, he had abandoned prose for poetry (for which he would also receive posthumous recognition) and soon afterwards Melville’s professional career as a writer effectively came to and end.

A year after Moby-Dick was published, Melville’s relationship with Hawthorne had also effectively come to an end. Much has been written and speculated about this most intriguing of literary friendships – a reading of Melville’s surviving letters to Hawthorne suggests a platonic love affair, at the very least – but Melville’s dedication of Moby-Dick should forever remind us that it is because they met that a masterpiece was born: “In Token of my Admiration for his Genius. This book is inscribed to Nathaniel Hawthorne.”

Pingback: Fatwah Bounty on Rushdie Raised; A Star-Studded ‘Moby Dick’ | Open Source Thinktank