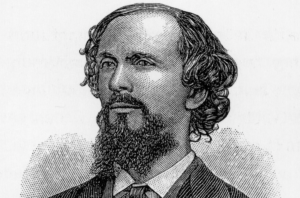

It was in the 4th century immediately after the Roman Empire became a de facto Christian state that the first anti-homosexual laws appeared. Thereafter, for the next 1500 years, the criminalisation of homosexuality spread voraciously and plague-like across the whole of Europe. So severe were the punishments that it was actually considered “progress” when in 1860 Great Britain reduced its penalty for homosexual acts from death by hanging to life imprisonment. So entrenched had this monocratic crusade become that no one dared challenge it. But on 29 August 1867 – and do please take note that this was over a century before Stonewall – 42-year-old German lawyer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs did just that. With his heart pounding and cognisant that “the distant gaze of comrades of my nature” was upon him, Ulrichs mounted the speaker’s box of Munich’s Odeon Theatre and, in front of 500 of Germany’s most esteemed jurists, pleaded for the repeal of anti-homosexual laws. Or, to be more accurate, sodomy laws – for Ulrichs’ action so far preceded the emergence of any LGBT movement that the word “homosexual” had not yet even been coined. The courage Ulrichs possessed is almost unfathomable. For this was not only the first public challenge to these noxious laws, it was the most open acknowledgement of the taboo concept of homosexuality witnessed anywhere in Europe since the days of Ancient Rome – and made by a self-proclaimed homosexual, no less!

Five years prior, Ulrichs had already declared himself to friends and family and in print an Urning (his own term for a man who desired another man), making him the first known gay man in the modern age to out himself. Ulrichs would go on to publish twelve pioneering works about sexuality, under his own name, including the first theory about homosexuality – arguing, against the religious notions of “corruption” and “perversion”, that same-sex love was in fact an entirely natural and in-born condition. Furthermore, Ulrichs’ vision extended far beyond the decriminalisation of homosexuality to nothing less than equal rights with heterosexuals.

Ulrichs’ plea to the Congress of German Jurists that day in 1867 was loudly shouted down. But, amongst the overwhelming cries of “No!” there were a few encouraging shouts to “Continue!” A small but momentous crack in the bulwark had been made. Just three decades later, the ground-breaking ideas of Karl Heinrich Ulrichs would inspire and launch a German gay-rights movement so advanced that we would not see its likes again until the 21st century. Fin de siècle Berlin emerged as the gay capital of the world. Ulrichs would directly inspire and influence German sexologist, Magnus Hirschfeld, who in 1897 founded the Scientific Humanitarian Committee – the world’s first gay and transgender rights organisation. Under the liberal Weimar Republic, gays were free from prosecution, gay-rights organisations flourished, Hirschfeld was permitted to openly conduct sex and gender studies (he calculated that there were 43,046,721 possible combinations of sexual characteristics). There were even early experiments in gender-reassignment surgery; in 1930, Hirschfeld himself supervised the first procedure of transgender pioneer Lile Elbe.

The arrival of the Nazis in German politics, however, brutally destroyed all such cultural advances, quashing those ideas that Ulrichs begat, then erasing his name from memory. Between 1933 and 1945, Hitler’s Nazi regime targeted more than one million homosexual Germans as part of their “purification” purge. An estimated 50,000 gay men were imprisoned – some of whom were sent to concentration camps, where SS lackeys used them for target practice, aiming at the pink triangles they were forced to wear. The Nazi persecution of homosexuals would not be fully acknowledged until 2002.

As for Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, after repeated arrests, he gave up his one-man battle and in 1879 fled to Italy. He died on 14 July 1895, not knowing that his works would become the foundation for gay-rights and non-binary activists. Despite enduring constant harassment, persecution and imprisonment, he had no regrets:

“Until my dying day I will look back with pride that I found the courage to come face to face in battle against the spectre which for time immemorial has been injecting poison into me and into men of my nature. Many have been driven to suicide because all their happiness in life was tainted. Indeed, I am proud that I found the courage to deal the initial blow to the hydra of public contempt.”