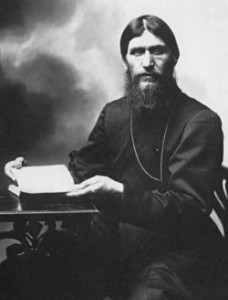

The death on this day in 1916 of Gregory Rasputin left a legacy as full of myth and misinformation – along with some bizarre truths – as his life had been. Poisoned with five times the usual lethal dose of cyanide, shot four times, strangled, beaten, bound in a carpet and thrown in a river – conflicting reports indicated that he died instantly from a gunshot to the head or that that he had survived all the assaults and drowned in the river.

The image of the virtually indestructible mad monk – a shaman with healing powers and a sexual hold over the Czarina – has entered into the mythology of the Russian Revolution. In popular memory, he has even occasionally been confused with the workers’ leader and sometime police agent Father Gapon. In reality there was nothing radical about Rasputin and he played no active part in revolutionary events – other than as a metaphor for the collapse of the old order in Russia.

Although Rasputin was never ordained as either a monk or a priest it is known that the son of a Siberian peasant did spend some time as a young man in a monastery – possibly as a punishment for horse-stealing. At some point it is generally thought that he came into contact with the Khlysts – a mystic Orthodox sect. The Khlysts stressed an esoteric personal path of enlightenment through redemption by having previously ‘known sin’ – and embracing ‘sin’ was seen as a first step in breaking down vanity and pride. Lurid tales of group sex and sado-masochism – along with their implicit challenge to Church authority – meant that the sect was widely disowned and condemned.

Whatever the truth of these tales, Rasputin with a voracious appetite for womanising and hedonism, found a natural home on the fringes of religion and became a self-proclaimed itinerant holy man and healer. Whether by using hypnotism as has been suggested in recent years, or by sheer force of his charismatic personality, the hard drinking peasant who refused to wash, gathered an unlikely following. This included several aristocratic women one of whom recommended him in 1905 to the Czarina Alexandra as being able to cure her son’s haemophilia.

So began a mutually fatal relationship with the Russian royal family: Rasputin may well have been able to ease the young prince Alexi’s condition – although modern interpretations would suggest more prosaic explanations than mystical healing powers: Rasputin drove away the court doctors – and with them their archaic practice of bleeding with leeches; he also stopped their prescriptions of the newly discovered wonder drug Aspirin. Both treatments we now know to be potentially fatal for haemophiliacs.

Whether or not as rumour and legend would have it Rasputin was the lover of the Czarina – he did come to have an extraordinary influence over her and increasingly over the Czar as well. They publicly acknowledged him as ‘our friend’ and started to quote his teachings and advice. In becoming their personal spiritual mentor he incurred the wrath of the Church leadership who repeatedly tried to have him removed. But even more significantly in becoming the royal family’s confidante, Rasputin became a hate-figure for the nobles at court, managing to unite traditionalist and the modernising factions in the aristocracy who both saw him as a threat. After the outbreak of war with Germany his relationship with the unpopular German-born Czarina made him unpopular with the wider public too. Their outrage was fed by a stream of sensationalist reports that painted him as a Charles Manson-like personification of all evil and debauchery. Possibly his behaviour became ever wilder when he developed an opium addiction after an attempt on his life by the disciple of a rival mystic in 1914.

Initially opposed to the war on religious grounds, Rasputin later advised the royal family that Russia could only be saved from defeat if the Czar personally took charge of the army. For Rasputin alienating all sections of the nobility, the church and the public was a fatal conjunction. Whatever the truth behind the legends of that night, when Prince Yuspov, Duke Pavlovich and Duma member Vladimir Purishkevich lured Rasputin to a palace cellar on the evening of 29th December 1916, they believed they were saving Russia from its greatest internal threat.

Although the conspirators did (eventually) succeed in eliminating Rasputin, they were wrong about the threat he posed: There were far larger forces at work that would soon bring down the old order in Russia. Possibly mindful of this, the aristocratic murderers were never tried and the Czar allowed them to quietly let them slip into obscurity.

Ironically soon afterwards the Czar tried to follow Rasputin’s advice and take personal control of the army – and in doing so triggered the crisis that led to his forced abdication and the revolutions of February and October 1917. Tellingly, the Bolsheviks subsequently felt it necessary to exhume Rasputin’s body and cremate it to prevent his grave becoming a place of religious pilgrimage – and to destroy an enduring symbol of the old superstitious Russia.

[Written by journeyman]

One Response to 29th December 1916 – the Death of Grigori Rasputin