“Our lives shall not be sweated from birth until life closes; Hearts starve as well as bodies; give us bread, but give us roses!”

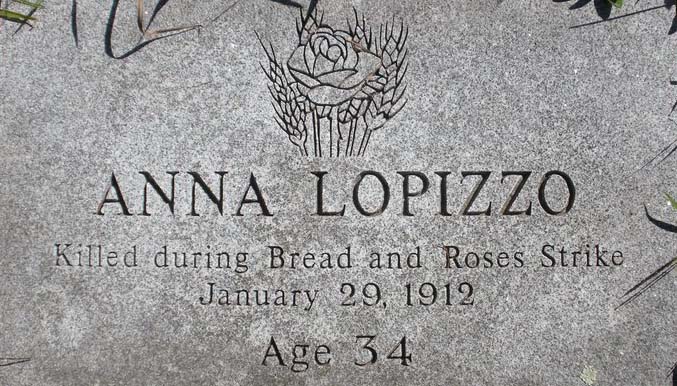

On this day in 1912, a 34-year-old female immigrant mill-worker was shot and killed by Massachusetts police whilst peacefully picketing in the Lawrence Textile Strike. Her name was Anna LoPizzo, and she was in no way remarkable. In life, she was not at the vanguard of reform or revolution. In death, she didn’t become a world-famous martyr. So anonymous was she that it’s not even certain “LoPizzo” was her actual surname. Like millions of other Europeans, she’d sacrificed all to cross the Atlantic in search of the American Dream – only to encounter gruelling hardships and a xenophobic caste system. But Anna’s forgotten story is central to one of the most significant strikes in labour history. For the Bread & Roses Strike, as it would famously come to be known, was the first American labour struggle to reject the age-old notion that women were lesser than men. And, just over 100 years later, it remains a sobering reminder of the divide between the ruling class and the rest of us.

In 1912, Lawrence, Massachusetts was a city of mostly poor immigrants who worked in the textile mills. Pay was piss poor, conditions were unimaginably brutal: dangerous machinery, suffocating dust, toxic fibres. Little surprise then that a third of Lawrence mill workers were doomed to die before they reached 25. A new Massachusetts law reducing women and children’s working weeks from 56 to 54 hours only provoked mill owners into deducting two hours of pay whilst demanding the same output. But this was a 30-cent pay cut: the equivalent of three loaves of bread! A group of Polish women walked out. Within a week, some 20,000 more mill workers – mainly women – had joined the strike in bold defiance of the gender and ethnic disadvantages their bosses so cruelly exploited. Leaders from the Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.) rushed to Lawrence to help organise the women. “They were valiant fighters,” recalled Elizabeth Gurley Flynn – the infamous Rebel Girl of the I.W.W. “The women wanted to picket.” So united were the strikers that their actions overturned industrialists’ long held assumptions that ethnically divided groups could not be organised. The mill owners responded by calling in the police and state militia, who turned fire hoses on the picketers and made mass arrests with much violence. Indeed, such was the gratuitous forcefulness that even Harvard students were invited to take up arms against the protesters – with the offer of course credits in return!

Two weeks into the dispute, on 29th January, dozens witnessed police officer Oscar Benoit firing the shot that killed Anna LoPizzo. But in a cynical move so typical of class struggles, the authorities charged I.W.W. organisers Joseph Ettor and Arturo Giovannitti with inciting murder – despite their both having attended a meeting three miles away at the time of the shooting. After Anna’s death, martial law was enforced and all public meetings declared illegal. Undeterred, the women continued to strike in LoPizzo’s memory. A month later, in a milestone victory, they won their wage increases.

But within just a few years, most of those gains would be lost. Not yet considered to be true Americans, Lawrence’s immigrant population now even distanced themselves as far as possible from the strike, for fear of being associated with the I.W.W. and branded anti-American – and with good reason! With the U.S.A. now involved in the First World War, members of the I.W.W. were rounded up and jailed, many even deported for having dared to espouse such supposedly unpatriotic ideologies as peace and better wages.

Over a century has passed since the Bread and Roses Strike, but how much has changed? Low-waged migrant workers remain the most vulnerable and exploited, while economic growth is still powered by the wealthy few. Moreover, with the shift in labour from industry to service, a new kind of oppression has emerged. In the past two decades, management has re-asserted dictatorial powers, while neo-liberalism has waged an all-out attack on unionisation. In his book The Great Divergence, author Timothy Noah comments:

“Draw one line on a graph charting the decline in union membership, then superimpose a second line charting the decline in [workers’] income share, and you will find that the two lines are nearly identical.”

Did men and women like Anna fight and die for the rights of humble workers only for their 21st-century descendants to live under corporate-driven, politically dominant plutonomies hell-bent on hoarding every last crumb?

4 Responses to 29th January 1912 – the Death of Anna LoPizzo