In the 1960s space was the final frontier. But just half a century earlier, the final frontier was the South Pole. And 104 years ago today – his two companions lying frozen to death next to him – 43-year-old Captain Robert Falcon Scott died in a tent in Antarctica, sheltering from a blizzard which had raged for nine days.

In recent years it has been fashionable to debunk the efforts of Scott and his men as a heroic failure. But I will have none of it. Scott and his men did reach the pole. And their expedition conducted ground-breaking scientific research which still resonates today.

Scott’s early Royal Navy career was uneventful. In the 1890s financial ruin and deaths in Scott’s family meant that at aged 30, he was now the breadwinner for his mother and two sisters. He had to find of a way of getting promoted. A chance meeting with Clements Markham, president of the Royal Geographic Society, would change his fortunes. He was accepted onto the trail-blazing British National Antarctic ‘Discovery’ Expedition. That journey from 1901 to 1903 mapped huge parts of Antarctica for the first time and made original observations in biology, geology, meteorology and physics. And they went further south than any person had been before: 82°17′S. The expedition was haled as a great success and Scott and his men returned as heroes. What wasn’t mentioned was that they failed to master the techniques of polar travel using skis, sleds and dogs. The Norwegians were already way ahead in this.

In 1908 Scott married artist Kathleen Bruce and their son Peter Markham Scott was born in 1909. Peter would later become a pioneer of wildlife conservation. However, the joy of his new family and the adulation of the British people were not enough to keep Scott from returning to Antarctica. He would take command of the Terra Nova expedition.

The expedition of 65 men would carry out a massive programme of scientific discovery, as well as attempt to reach the South Pole. Japan and Australia were also planning Antarctic journeys. The Norwegians seemed not to pose a threat as, publicly at least, they appeared to be concentrating their efforts in the North. The Brits had best get on with it or someone else would grab the glory. But on their way south, while Scott was in Melbourne, he received a telegram from Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen telling him that he was heading south. The race was on.

Amundsen’s only mission was to reach the Pole. With skis and dog sleds, his men dressed in skins and furs like the Inuit, he would use the highly efficient ‘dog-eat-dog’ technique as he went along to provide fresh meat. Scott’s polar plans were more complex and included establishing a research base, testing motorised sledges, and using ponies, dog sleds and man-hauling to carry provisions, scientific instruments, log books and specimens.

Scott and his men spent 1911 establishing a base at Cape Evans and laying depots of provisions. Parties were sent out on missions to make geological surveys and collect specimens. They experimented with equipment and rations. Their findings would influence polar explorers and mountaineers for decades. A zoological expedition set out in the winter to conduct research on emperor penguins to try to discover an embryological link between the birds and dinosaurs. Apsley Cherry-Garrard who took part in this expedition later wrote an account of it in his astonishing book The Worst Journey in the World.

In September, 16 men set out towards the Pole. Most of the men were there as support and would be sent back in stages leaving only a small group to go all the way to the Pole. At 87° 32′ S on 3 January 1912, Scott decided on the group: himself, Edward Wilson, Lawrence Oates, Henry Bowers and Edgar Evans. Five men, not four as originally planned. This meant recalculating rations and would have dire consequences.

They arrived at the Pole on 17 January, but Amundsen had planted his flag there a month before. The disappointment was overwhelming. “Great God! This is an awful place” Scott wrote “and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority.”

The return journey started out well. But the rations were insufficient and his men soon lost condition. Evans’ frostbite worsened. He died at the the Beardmore Glacier on 17 February. Oates’ feet were horribly frostbitten and hampered the progress of the entire party. On 16 March, he struggled to put his boots on for the last time and stepped out into a blizzard saying, “I am just going outside and may be some time.” Scott acknowledged his sacrifice. “We knew that Oates was walking to his death… it was the act of a brave man and an English gentleman.”

Scott, Wilson and Bowers continued towards One Ton depot which they knew could save them, but an unseasonal blizzard halted them just 11 miles short of their target. Malnourished, frostbitten, weak and trapped inside the tent by the weather, they knew what was coming.

“I do not think we can hope for any better things now. We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far.”

Scott was probably the last of the three to die on 29th March 1912.

A search party found the tent in November that year. They salvaged rolls of photographs, meteorological observations, diaries and 16 kgs of fossils gathered on the way back from the Pole. They left the bodies in the tent and buried them under a mound of snow.

That five men failed to be first to the Pole and died is only half the story. The expedition recorded more than 2,000 animals, 400 new to science. They gathered rock samples and fossils which revealed the geological story of the Antarctic continent. They made detailed observations in glaciology, meteorology, geology and studied diet, clothing and rations in extreme conditions. Cherry-Garrard wrote: “We had within our grasp material which might prove of the utmost importance to science; we were turning theories into facts with every observation we made.”

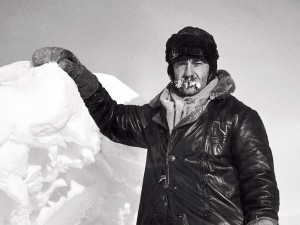

And apart from the science, there was the art! Herbert Ponting’s photographs recorded the grandeur and the hardships. And Edward Wilson’s illustrations of Antarctic birds and wildlife are unsurpassed.

One hundred years after Scott we now face climate change, melting icecaps, rising sea levels, weird weather phenomena and a crisis of extinctions. Polar science is now more important to us than ever in helping us work out what is going on and what – if anything – we can do about it. And Captain Scott was, surely, one of the founding fathers of polar science.

“Had we lived, I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance, and courage of my companions which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman. These rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale…”

[Written by Jane Tomlinson]