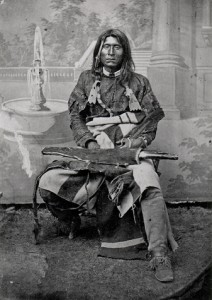

Today we remember the Native American chief of the Modoc tribe, Kintpuash – known by his foes as “Captain Jack” – hanged by the United States army on this day in 1873 in retribution for killing an American general. But that’s the white man’s side of the story. In truth, Kintpuash – like so many of his fellow Native American chiefs – was the dual victim of a greedy American government hell-bent on expansionism as well as his own desperate people. In the face of increasing hopelessness, Kintpuash’s fellow warriors were to force their leader into a decision so misguided that when an aggrieved American army finally captured him they sought bitter revenge by staging an execution so lacking in dignity that souvenir mongers were allowed to collect pieces of the hanging rope and locks of Kintpuash’s hair. In the final indignation, the great Indian chief was decapitated – some reports suggest that his head was then sent to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.; others claim it made the rounds of carnival side shows. But despite his tragic end, Kintpuash is best remembered for leading his people to a cunning and legendary victory in the Modoc War of 1872-73. So let us recall the events that led to “The Battle of the Stronghold” and, ultimately, Kintpuash’s death.

Robbed of their ancestral land on the Northern California/Oregon border and subsequently denied their own reservation, the Modoc people were finally pushed too far when they were expected to live alongside a hostile tribe. Retreating from the US Cavalry, Kintpuash led his people to a high rock plateau of lava beds with sharp-edged outcrops and deep cracks: the Modocs knew it as “Land of Burnt-Out Fires”, the cavalrymen called it “hell with the fires gone out”, but it would soon come to be known as “Captain Jack’s Stronghold”. A labyrinth of connected trenches provided a near impregnable defensive position – nevertheless, the army’s commanding officer, Lt. Col. Frank Wheaton, expected a swift victory. At dawn on January 17th 1873, Wheaton’s troops advanced on the lava beds. But out of nowhere, a dense fog appeared; unable to see more than six inches in front of them, the soldiers called out to one another and exposed their position to the Modocs. The Indians knew their terrain so intimately that the fog caused them no trouble; they veiled themselves behind the rocky outcrops and waited until they were able to open fire at close range. At the end of the day, 53 Modocs had inflicted a heavy defeat upon 400 U.S. troops. A humbled Wheaton, who had commanded an army of 20,000 at the Battle of the Wilderness during the Civil War, reflected, “I have never before encountered an enemy, civilized or savage, occupying a position of such great natural strength as the Modoc stronghold, nor have I ever seen troops engage a better-armed or more skillful foe.”

Intermittent fighting and failed negotiations continued for the next three months, as the US government rejected each and every Modoc proposal for their own reservation. Kintpuash lost patience and support amongst his warriors, who demanded that they kill the peace commission leadership at the next negotiating meeting. At the parley on Good Friday, 11th April 1873, Kintpuash asked General Edward Canby to withdraw. The general refused. Then, goaded by his fellow warriors, Kintpuash pulled out a pistol and killed Canby and another peace commissioner.

Reprisal was swift. 1000 troops were deployed to “exterminate” the Modocs who, despite their position being betrayed by some of their own, held out for nearly two more months before they were eventually forced out of their stronghold. After Kintpuash surrendered, the War Department granted him a trial but didn’t bother providing him with a lawyer. So sealed was his fate that workers built a gallows outside in full view of the courtroom as the trial began. Hooker Jim, a Modoc warrior, provided the damning evidence. Kintpuash and five other Modoc leaders were found guilty of war crimes – a charge unique in all of the Indian Wars – and sentenced to death. When asked if he had anything to say, Kintpuash responded: “You white people did not conquer me. My own men did.”

Following the war, the surviving Modocs were sent to a reservation in Oklahoma until 1909 when the few remaining tribes people were permitted to return to Oregon. It is estimated that the Modoc War cost the United States $4,000,000. The cost of the land the Modocs wanted for their own reservation was $20,000.

13 Responses to 3rd October 1873 – the Death of Kintpuash