Today we recall the Haymarket Affair – the most sensational American labour incident of the 19th century, whose legacy even today continues to surreptitiously reverberate. What began as a nationwide movement for the 8-hour work day on 1st May ignited just a few days later during a peaceful rally in Chicago and ended eighteen months later with the hanging of four innocent men. The Haymarket Affair would deepen the divide between labourers and the new ruling class of industrialists, expose the fallacy of free speech and the American justice system, exacerbate the anti-immigrant sentiment and tarnish the labour movement irrevocably.

“Eight hours for work. Eight hours for sleep. Eight hours for what we will.” So how did it come to pass that this wholly reasonable demand for an 8-hour work day would result in such devastating and consequential tragedy?

After the Civil War, the United States underwent a period of unparalleled industrial growth. Men became rich and famous building new industries and establishing vast corporate empires. But this new wealthy elite had no interest in sharing their gains with the workers who made their terrific success possible. In response to near-slave conditions – 16-hour workdays, pitiful pay, unsafe and unregulated environments – disgruntled workers began to mobilise.

May 1st 1886 was decreed by the federated unions as the date when workers throughout the country would join together to demand an 8-hour work day. In Chicago – the hub of the nascent labour movement – a day of demonstrations passed without incident. But just two days later during strike protests at the appropriately-named McCormick Reaper Works, trigger-happy policemen fired indiscriminately into a crowd that included women and children, killing several workers. August Spies, editor of the German pro-labour newspaper the Arbeiter-Zeitung, witnessed the attack firsthand. In response, he printed and distributed a leaflet calling for a meeting the following evening to denounce the police violence.

On the drizzly night of 4th May 1886, over 2000 gathered in Chicago’s Haymarket Square to protest the murders at the Reaper Works. The peaceful rally had nearly concluded when – without provocation or warning – police advanced towards the speakers’ wagon demanding immediate dispersal. At that precise moment, a bomb was thrown from within the crowd. PC Mathias Degan died instantly, and seven other officers were killed by “friendly fire” after the well-armed police countered like headless chickens. Over a hundred demonstrators were injured, an “unknown” number of them killed.

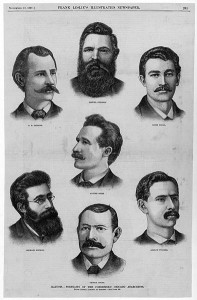

Mass hysteria ensued. With the near unanimous backing of the public and media, the authorities set out to crush the labour movement – which it tarred with the generic brush of “anarchism” led by “reckless foreign wretches” who threatened the very core of American institutions with their dirty radical ideas. Martial law was declared. No more than two people at a time were allowed on street corners; union newspapers were closed down; and – in what amounted to America’s first “red scare” – police raids overstepped all legal authority as hundreds of labour leaders were rounded up and arrested. Eight of Chicago’s most prominent anarchists were charged with the murder of Officer Degan, despite the fact that most of them hadn’t even been present during the incident. Without any evidence to connect the defendants to the bomb throwing, Anarchism itself was put on trial. Illinois law stated that anyone inciting murder was guilty; the Chief Prosecutor implored the jury to “make examples of them. Hang them, and you save our society.” The jury duly returned guilty verdicts for all eight defendants; all but one sentenced to death. Two had their verdicts commuted to life imprisonment, one committed suicide in his prison cell, but – despite worldwide condemnation and calls for clemency – on November 11th 1887, the four remaining anarchists were executed in a particularly brutal hanging by slow strangulation in full view of shocked witnesses.

August Spies, Albert Parsons, Adolph Fischer and George Engel are remembered as the Haymarket Martyrs – executed for their radical ideas perceived to be fundamentally un-American: Fair working conditions. A greater sharing of the wealth for a workers’ own toil. Exposing state repression. Unionisation. Resisting the cynical attempts to drive a wedge between native-born workers and immigrants. “Anarchism does not mean bloodshed; it does not mean robbery, arson, etc.,” wrote August Spies. “These monstrosities are, on the contrary, the characteristic features of capitalism. Anarchism means peace and tranquility to all.”

The Haymarket Tragedy sparked protests around the world and galvanised a new generation of radicals and revolutionaries. It was the political awakening of such stalwarts as Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman and Voltarine De Cleyre. But despite the radical agitators Haymarket impelled and a momentous wave of strikes in its aftermath, in truth the American labour movement never fully recovered from the backlash. For when it came down to it, the masses didn’t want “revolution.” They didn’t want autonomy. They just wanted a few measly crumbs. And as soon as those in power figured that out, they stopped fearing revolt and the pendulum shifted forever in their favour.

The enduring tragedy of Haymarket is that no single event did more to destroy the American labour movement, and we can only rue the lost opportunity to eradicate the evils of embryonic capitalism. Today, Western workers are at the mercy of the global free market, dominated by neo-liberal corporations who care not one jot for the individual. “Union” is once again a dirty word. The 8-hour day – the very thing the Haymarket workers were demonstrating for – doesn’t even seem inviolate any more. To be anti-capitalist is to be un-American. And the story of the Haymarket Affair has been all but erased from American history.

A monument to the Haymarket Martyrs Monument has been federally dignified as a National Historic Landmark, despite the fact that there has never been a posthumous pardon for the four executed innocents.

It was never discovered who threw the bomb.

One Response to 4th May 1886 – the Haymarket Affair