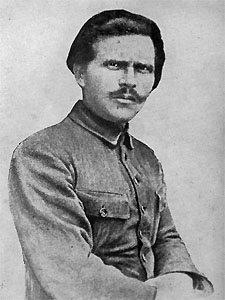

Today we recall the Ukrainian revolutionary leader, Nestor Makhno, who died on this day in 1934 in poverty, illness and oblivion. Fellow exiles who’d watched Makhno drink and cough himself to death in the slums of Paris could scarcely believe the tragic fate that had befallen the legendary “Little Father” of Ukraine who, just fifteen years earlier, had been one of the most heroic, glamorous and indefatigable figures of the Russian civil war and the inciter of one of the few historic examples of a living anarchist society. As the leader of the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine, this self-educated peasant-born military genius had waged a wildly creative guerrilla war against native tyrants, foreign interlopers and counter-revolutionaries. On behalf of what was always an uneasy alliance with the Red Army, Makhno’s forces had twice immobilised the seemingly unstoppable White advance in South Russia; indeed, so decisive were these against-all-odds victories that the Bolsheviks might never have won the civil war and consolidated power but for Makhno and his insurgent peasants. As the instigator, military protector and namesake of Ukraine’s simultaneous anarchist revolution – the Makhnovshchina – few have come closer than Nestor Makhno to establishing an anarchist nation. For nearly a year between 1919 and 1920, some 400 square miles of Ukraine was reorganised into an autonomous region known as the “Free Territory” in which farms and factories were collectively run and goods traded directly with collectives elsewhere. In his heyday, Nestor Makhno was an unmitigated living legend and folk hero – a real-life Robin Hood and proto-Che. But by the time of his death at the age of forty-six, so comprehensively dragged through the filthiest, shittiest mud was the name of this once unassailable revolutionary that it has yet to fully recover.

So what happened?

In 1917, 29-year-old Nestor Makhno was released from a Tsarist Russian prison where for nine years he’d been chained hand and foot until liberated by the February Revolution. He returned to his Ukraine homeland to begin a peasants’ movement, expropriating land from the wealthy few to redistribute to the many poor. But when the Bolsheviks sold out Ukraine and handed it to the Germans and Austrians in the 1918 treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Makhno’s band of peasants were redeployed as guerrilla warriors who somehow managed to expel the interlopers within a year. By this time Makhno’s reconstructed anarchist society covered most of the Ukraine, in the face of strong opposition from Moscow. In the ensuing chaos, the Revolutionary Insurrectionary or Black Army fought a bewildering multi-front civil war – sometimes against the Reds, sometimes against the Whites, sometimes with the Reds against the Whites. After the Whites were defeated, Lenin and Trotsky conspired to destroy Makhno’s army – the very forces that had enabled the consolidation of their own power. The Bolsheviks even went so far as to prepare an ambush by inviting the officers of the Crimean Makhnovist army to take part in a military council, where they were immediately arrested and summarily executed.

The then all-mighty Trotsky ordered Makhno’s assassination on sight. Makhno eluded his pursuers for nearly a year, but was soon forced into retreat as the full weight of the Red Army and the Cheka bore down on him. Makhno managed to escape to Paris via Romania and Poland. Having failed to kill him, the Bolsheviks determined instead to morally destroy him – branding him a bandit, counter-revolutionary and worst of all a rampant anti-Semite Jew killer. Never has any proof emerged to support these accusations. Rather, there is an abundance of evidence to the contrary. Makhno possessed numerous close Jewish comrades (all of whom vigorously defended him), had issued proclamations forbidding pogroms and even personally and publicly executed the chief of a White band of notorious pogromers as an object lesson.

But the Bolsheviks had their way. The unceasing stream of Soviet-orchestrated slander, vilification and propaganda in the form of history books, novels, short stories and even a spurious diary of “Makhno’s Wife” succeeded in blackening the Ukranian hero’s name for the rest of his days.

As he lay dying from tuberculosis in a Paris hospital, it would have been scant consolation to Makhno that the architect of his ruin – Trotsky – was in the same city, by then also betrayed and driven out of Russia into exile.

Pingback: Eighty years ago: the death of Nestor Makhno | Poumista