On this day in 1857, African-Americans were delivered a conclusive and seemingly fatal blow to their prospects for freedom. It was official. The United States Supreme Court – the highest bastion of law and morality – ruled that ‘Negroes’ were not people. They were property. And this was their truth wherever they stood on American soil, even in so-called “free” states. Dred Scott v. Sandford is more than a landmark case in America’s history. The decision would prove to be a catalytic event with catastrophic consequences. With this ruling, six justices decided that the fate of America would lead inexorably to civil war.

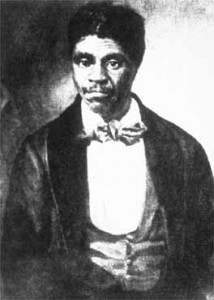

Eleven years earlier, Dred Scott – an illiterate slave – had sued for his liberty in a Missouri court, holding that he had by rights become free after residing for a decade in the free North with his now deceased master before being returned to the slave state of Missouri. So contentious was this case that it eventually went all the way to the Supreme Court for its ruling on three critical issues: (1) whether Scott was a citizen of Missouri and thus entitled to sue in a federal court; (2) whether his sojourn in free territory had made him legally a free man; and (3) the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise – the agreement passed in 1820 between the pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions in the United States Congress to regulate slavery in the western territories.

On March 6th 1857, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney delivered the majority opinion of the nine justices – five of them southerners – of the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of Dred Scott v. Sandford. By a majority of seven to two, the Court ruled that – as a Negro – Scott was not a citizen Missouri or indeed the United States, and therefore had no right to bring suit in the federal courts on any matter; Scott had never been free because slaves were personal property; and, furthermore, the Missouri Compromise of 1820 had in fact been in violation of the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution: a person’s right to life, liberty and property. Except the rights being violated were not a black person’s right to life and liberty; but, rather, a white person’s right to property, i.e. slaves.

Delivering this crushing verdict, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney did not stop there. In one of the most odious and shocking statements ever recorded in an American Supreme Court decision, the slaveholding chief justice from Maryland declared that blacks were “beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery.”

In deciding the fate of one man’s claim for freedom, the Supreme Court delivered a verdict on the entire – and highly divisive – issue of slavery. This broad decision, largely engineered by the recently inaugurated President James Buchanan, gave the South everything it had hoped and long argued for. Henceforth, the Federal government would have no authority to exclude slavery from any U.S. territory. The North, however, responded in outrage. Northern abolitionists – utterly astonished that the court had invoked the Bill of Rights to deny a man his freedom – refused to accept the ruling against African-American citizenship and its denial of congressional authority over the territories. For African-Americans, the devastating verdict was met with hopelessness and – as Frederick Douglass put it – “manifold discouragements.” But for the fledgling Republican Party coalition of the North, the decision served to crystallise their purpose. Founded in 1854 to prohibit the spread of slavery, the Republicans now renewed their fight to gain control of Congress.

And in Illinois, Abraham Lincoln – a relatively obscure railroad lawyer and one-term Congressman – was compelled to re-enter politics solely to denounce the ruling. Lincoln was far from an abolitionist; early on in his career, he famously held his own racist views. But he, like the rest of the Republicans, could not abide the Dred Scott decision. Abraham Lincoln no longer had a choice. John Brown no longer had a choice. As Civil War historian Professor David Blight explains:

“[The decision] destroyed any conception of consensus or compromise … and that’s when you see danger in American political history … when the side that loses a debate cannot accept the result.”