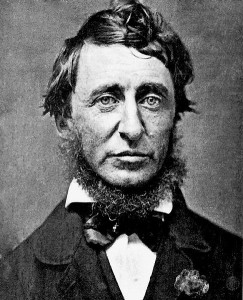

Today we pay tribute to author, naturalist, abolitionist, poet, prophet and unrepentant individual – Henry David Thoreau. When he died on this day in 1862 from tuberculosis aged 44, this giant in the American pantheon was still virtually unknown. Indeed, when delivering his eulogy, Thoreau’s great mentor, fellow Transcendentalist and best friend Ralph Waldo Emerson lamented: “This country knows not yet, or in the least part, how great a son it has lost.” Today, however, the once-neglected life and works of Thoreau resound with an almost Nostradamus-like prescience: environmentalist, direct activist, insurrectionist, anti-materialist, advocate of self-sufficiency, individualist, intuitive anarchist – 150 years after his death, Thoreau’s polymathic footprints are surely amongst the most relevant and useful. Since his “rebirth” in the mid-twentieth century, Thoreau’s natural history and polemical writings have significanlty influenced environmental movements and the struggles of the world’s oppressed. His anti-authoritarian convictions profoundly inspired Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr. and the anti-Vietnam generation. His retreat from the material world to seek a more meaningful life close to nature is an apposite blueprint. Ecologists, naturalists, radical reformers and libertarians alike thus claim him as their own. But as one of the great champions and prophets of self-reliance and individualism, Thoreau in truth belongs to all who are governed by passion, principle and purpose. “Most men lead lives of quiet desperation and go to the grave with the song still in them,” he wrote. Throughout his too-short life, Thoreau sought instead to forge a path that refused compromise – to “follow the beat of a different drummer.”

Born and bred in Concord, Massachusetts – the town where the first shot of the American Revolution was fired and, as the hub of the American Transcendentalists, the epicentre of the young nation’s “second revolution” – Thoreau’s universal philosophy emanated entirely from his local surroundings. An almost mystical naturalist, scholar of Native American lore, eminent botanist and skilled surveyor, Thoreau walked every day with his eyes wide open and knew every tree, plant, animal species and river around Concord. A proto-practitioner of “think locally, act globally,” for Thoreau, there was no separation between Nature and the conduct of life. Disdainful of America’s growing commercialism and industrialism (he foresaw environmental disaster with the growth of railroads; the telegraph, he predicted, would lead to the inane obsession with idle gossip), on the 4th of July 1845 – as his fellow countrymen celebrated sixty-nine years of independence – Henry David Thoreau famously walked out of Concord to live in solitude in a self-built hut two miles outside of town on Emerson’s land in the woods. The resultant account of this extraordinary two-year experiment in observation and simplification – Walden, or Life in the Woods – conveys at once a naturalist’s wonder at the everyday and a Transcendentalist’s quest for inner spirituality, self-reliance and personal freedom:

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion.”

But even in the very midst of this gnostic adventure, Thoreau never entirely separated himself from worldly matters. Whilst venturing into town one day for supplies, he was incarcerated for refusing to pay poll tax to the commonwealth of Massachusetts in protest of the state’s endorsements of slavery and the Mexican War. Although he spent only one night in jail (much to his chagrin, the next morning an unknown benefactor cleared his six-year tax debt), it caused him to wonder why it is that we obey laws without asking if they are just. And, worse still, why others will obey even if they know them to be wrong. The experience resulted in “Civil Disobedience” (or “Resistance to Civil Government”, as it was first titled in 1849). A polemic on the individual’s right, nay duty, to dissent from government policies in accordance with his or her own conscience – “Disobedience is the true foundation of liberty” – it would in the twentieth century become one of the most famous and important essays in American literature.

It is impossible to shoehorn the numerous and disparate key points of Thoreau’s life; as the emblematic practitioner of Transcendentalism, his life itself was the key point. He cleaved to no system, trusting only his inner morality. And for we Moderns, few ancestral voices speak with a greater truth. As our governments continue to trespass on our personal freedom, he reminds us that we are at liberty and indeed duty-bound to follow our own convictions. As the excesses of globalisation continue to wreak havoc on our planet, he is our great champion of simplification. And in this age when we are sorely lacking visionaries to lead the way, what a comfort it is to find such eternal wisdom and solace in the words and deeds of Henry David Thoreau.

7 Responses to 6th May 1862 – the Death of Henry David Thoreau