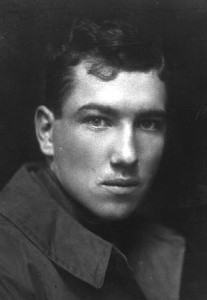

Today we pay tribute to the extraordinary English poet, novelist, translator and scholar, Robert Graves – a literary giant, who died thirty-two years ago on this day. Seemingly effortlessly, Robert Graves’ career straddled vast tracts of time, his biography featuring such diverse accounts as poet Siegfried Sassoon’s World War One trench madness to playing host to the Soft Machine at his Majorcan home in the late 1960s. Like William Burroughs, Graves is ubiquitous in Western culture. He made his name as a war poet, then authored arguably the finest autobiography of the Great War in Good-Bye to All That. To most, Graves’ legend was already assured but he had barely begun. In his bestselling book I, Claudius, Graves gave us the most widely known and influential historical novel of his time. He dared to redo the Greek myths, and nowadays his are the orthodox editions. Collaborating with Jewish scholar Joshua Podro, Graves published the 982-page The Nazarene Gospel Restored, which systematically and painstakingly compared all of the orthodox gospels with those sacred texts omitted from the New Testament, proving that much of Jesus Christ’s teachings were not in opposition to his Jewish forebears as Saint Paul’s version likes to make out. Robert Graves had always viewed the debasement of women and the overwhelming and overweening patriarchal values of Western society as the two basic flaws from which he felt we should free ourselves. But it was not until the 1948 publication of The White Goddess, that Graves set down in a somewhat hysterical black-and-white, his controversial belief that civilisation had romped forwards in progress only when it had overwhelmed the previously all-powerful matriarchal societies. And despite the scholarly backup and scientific evidence of The White Goddess having been rigorously contested down the scores of years since its publication, it has been this curious little book – subtitled “A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth” – which has, with all its attendant insights and brain-capers, continued to illuminate the ways of poets and artists of subsequent generations. It is to be hoped that Graves himself would have been most delighted by this poetic turn of events, for he considered himself first and foremost a poet, and novels such as I, Claudius as mere wage-earners: “Prose books are the show dogs I breed and sell to support my cat.”

[Written by Saoirse Ó Gradaigh]

One Response to 7th December 1985 – The Death of Robert Graves