At one minute before midnight on December 28th 1937 the Irish constitution passed into law and the Republic of Ireland (or Éire) was born. Although it has been described as a revolutionary act itself, the passing of the constitution was a strangely muted – almost administrative – conclusion to several hundred years of oppression and bloody rebellions.

It was the middle of the 12th century when the first Cambro-Norman troops arrived on Irish soil from Britain, but it wasn’t until after the English Reformation in the 16th century that the British government asserted ownership of the island of Ireland and attempted to impose absolute control. Prior to that time the foreign presence was resented, occasionally opposed, but ultimately tolerated by the native people who owed little or no allegiance to the invaders but equally whose lives were not significantly influenced by them. It was only when the British Crown renounced Catholicism and instigated the twin policies of Plantation and the Penal Laws in Ireland that the life of the average Irish person was dramatically impacted by the British presence. Consequently, it was only then that rebellion against the Crown became widespread.

The policy of Plantation essentially robbed the Irish peasantry of their land, handing over all but the least fertile tracts to English and Scottish colonists and turning small-hold farmers into tenants of often oppressive landlords. At the same time the Penal Laws aimed to obliterate all traces of traditional Gaelic culture from the island by denying basic rights to Catholics – to the point of outlawing the celebration of the Catholic Mass – and suppressing, even violently, the speaking of the Irish language along with traditional art, music and sports. And so began more than 350 years of conflict that was to culminate in the Easter Rising of 1916 and the War of Independence it sparked.

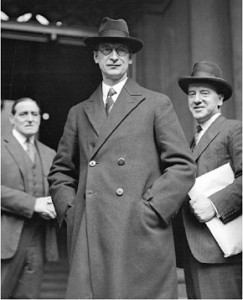

One of the leaders of the 1916 Rising was Éamon de Valera, in many ways – for better and for worse – the dominant figure of 20th-century Ireland. Despite being the subject both of hagiography and demonization, de Valera ultimately resists such simplistic black-or-white characterisation. Though eventually becoming a divisive figure, de Valera’s vision and determination helped unite the Irish in their struggle against British rule after the Easter Rising. With the end of the War of Independence in 1922 and the establishment of The Irish Free State (a semi-independent Dominion of the British Empire), he led the defeated faction in the subsequent civil war — refusing to accept the partitioning of the island, de Valera sought to continue the War of Independence until Ireland was united under a single government.

Despite leading the losing side of the civil war, de Valera’s determination (and many would say, his deviousness) saw him rise to the position of Prime Minister of the Free State in less than a decade. He acknowledged the grim irony of being leader of a Dominion State that he himself viewed as illegitimate and almost immediately upon taking office in 1932 instigated the process of severing all ties with London. He had a vision of an Irish Republic that was at once radical and conservative, blending revolutionary socialism and reactionary Catholicism in a unique and perhaps paradoxical fashion. Some have gone so far as to argue that de Valera’s zealous participation in the Easter Rising (his was the last of the brigades to surrender), his imprisonment, being sentenced to death (commuted just hours before he was due to be shot) and his involvement in the bloody wars that followed had left him shell-shocked and that his subsequent political philosophy was tinged with genuine madness.

He would not be the first revolutionary leader to suffer such a fate. And certainly not the last.

So it was that during the 1930s de Valera supervised the drafting of the Constitution of the Irish Republic. It is a document infused with socialism and Catholicism; a document that cautions against the creep of global capitalism and seeks to establish Ireland as a genuinely independent and self-sufficient nation… a society anchored with deep roots in the past that would consciously isolate itself from an outside world committed to a progress that de Valera viewed with suspicion and contempt.

In July 1937 de Valera called a referendum and the Constitution was adopted by the people of Ireland, though with a smaller majority than he had expected. The divisions of the civil war had not healed and while most Irish welcomed the establishment of a Republic, de Valera’s zeal was viewed with some disquiet. There was recklessness in his refusal to negotiate a separation with the British government, and his determination to simply announce the Republic unilaterally conjured fears of a military backlash from across the Irish Sea.

In the end however, with the storm clouds of fascism gathering across Europe, Britain could ill-afford to become embroiled in yet another guerrilla conflict to its west. So when the Constitution was written into Irish law 73 years ago today, it provoked nothing more than a stern letter from His Majesty’s Government in London.

And so the people of Ireland became Citizens of a Republic; no longer Subjects of a Crown… half-led, half-dragged by a willful visionary; a brilliant man driven to the edge of madness by power and violence.

By the 1960s Éamon de Valera’s vision of Ireland was considered antiquated. Backwards even. Certainly his determination that Ireland should be a beacon of Catholicism (the Constitution he produced was even sent to the Vatican for approval prior to the referendum) ultimately bestowed far too much power on the clergy which — as is ever the case — became corrupted and perverted by it. Similarly, de Valera’s insistence upon cultural isolation, nay cultural purity, was probably neither desirable nor realistic.

However, those who have condemned de Valera’s ideas as totally flawed are doing him a great disservice. There is much about his vision that, far from being antiquated, was well ahead of its time. His deep suspicion of global capitalism and of industrialisation (he considered it destructive and unsustainable) and his insistence that Ireland – that any nation – should be self-sufficient, capable of feeding, clothing, housing and educating their citizenry without external assistance will, I am convinced, soon be seen as genuinely forward-thinking… once the project of globalisation is exposed as the house of cards it truly is.

[Written by Jim Bliss]

2 Responses to 28th December 1937 – The Birth of the Irish Republic