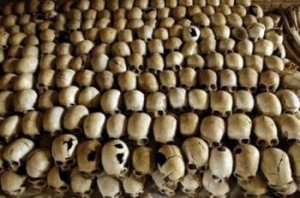

On 6th April 1994, the plane carrying Rwandan president Juvenal Habyarimana was shot down by surface-to-air missiles as it approached Kigali Airport. All on board were killed. The responsibility for the downing of the plane remains a mystery, but the assassination of Habyarimana has gone down in history as the spark that set the Rwandan Genocide in motion. As early as 1992, Hutu extremists had devised a genocidal plan complete with names and addresses of proposed victims – and within forty-five minutes of the president’s assassination, machete-wielding death squads were marauding through the streets of Rwanda’s capital, systematically butchering the leaders of the predominantly Tutsi Liberal Party, the multi-ethnic Social Democratic Party, cabinet ministers, justices of the constitutional court, journalists, human rights activists and progressive priests. The next morning, the presidential guard assassinated the Prime Minister, Agathe Uwilingiyimana, along with ten Belgian UN troops who had been guarding her. But even this violent killing spree gave no real indication as to what would happen next… for in the ensuing one hundred days, nearly one million Tutsis and Hutu moderates would be murdered by Hutu extremists in a wave of brutal, unrestrained and unprecedented carnage – the killing rate was five times faster than that of the Nazis during WWII holocaust. But while the rest of the world could claim ignorance of Hitler’s extermination camps with at least a modicum of credibility, the Rwandan Genocide happened with the full knowledge of the UN Security Council, the Western governments and the international media.

It would, on the face of it, be arrogant for we in the West to attempt an understanding of the tribalism at the root of this unfathomable tragedy – except that the hatred was in truth not so very deep-rooted, as its seeds were sown only one hundred years previously by Rwanda’s European colonisers. During the so-called “Scramble for Africa” in the last quarter of the 19th century, the kingdom of Rwanda was claimed by Germany – and the German colonists foisted their race obsession on this tiny, beautiful country whose landlocked position had hitherto protected it from foreign infiltration. The German colonisers discovered a remarkably advanced and organised agricultural society: for at least four centuries, Hutu and Tutsi had coexisted peaceably – sharing the same language, worshipping the same gods and intermarrying. The Germans, believing blacks incapable of developing such a sophisticated society, expanded a variety of illogical rationales that the tall, fine-featured Tutsi were a superior race – descended from Ethiopia, Egypt, Tibet, or even Atlantis. The Germans bestowed the Tutsi with privilege and education – and through them instituted indirect rule; any punishment to keep Hutu in line was carried out by Tutsi. The later Roman Catholic missionaries and Belgian colonisers continued to propagate the myth of Tutsi superiority. Belgian ethnologists analysed thousands of Rwandans on analogous racial criteria and issued every Rwandan with an ethnic identity card. This introduction of Western racism and class-consciousness unsettled the stability of Rwandan society. Tutsi behaved as aristocrats, believing themselves physically and mentally superior, while the allegedly inferior Hutu were deprived of all political and economic power and treated as peasants. An alien political divide was born, and an ethnic time bomb began to tick.

Western powers must bear criminal responsibility for Rwanda’s genocide not only for sprouting it, but also for their disgraceful failure to prevent and stop it. The United States, Britain, France, Belgium, the Roman Catholic Church and the UN: for their failure to intervene, all are guilty. “The international community didn’t give one damn for Rwandans because Rwanda was a country of no strategic importance,” said General Romeo Dallaire – the commander of the U.N. peacekeeping force in the country at the time. Despite calls from Dallaire for reinforcements, the UN Security Council voted to cut the UN presence from around 2,500 to a token force of 270, largely because the United States feared becoming entangled in an intractable conflict in the wake of its disastrous intervention in Somalia. From the beginning of the violence, the international community promulgated a clear message that it was disinterested and would not act to stop the massacres in Rwanda.

So deliberate and cynical was the West’s evasion that, as the horror unfolded, America and Britain even sought to block the use of the word ‘genocide’ – for, under the terms of the 1948 Geneva Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide, this would have obliged them to ‘prevent and punish’ those responsible.

But what happened in those 100 days from April 6th to July 17th 1994 constitutes one of the most evil and purest manifestations of genocide in our time, meeting all the criteria set down in the Geneva Convention. This wasn’t supposed to happen again, but it did. “One death is a tragedy, a million is a statistic,” said Joseph Stalin. As evidenced by the West’s racist and selective non-response to the Rwandan Genocide, the tyrant never spoke truer words.

5 Responses to 6th April 1994 – the Rwandan Genocide Begins