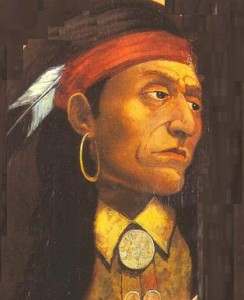

On this day in 1763, one of the most significant Indian rebellions in the history of Colonial America began when a confederacy of tribes under the leadership of Chief Pontiac attacked British forces at Fort Detroit. Pontiac’s war would rage for nearly two years before an uneasy truce was reached – but the consequences would prove to be even more dramatic than the rebellion itself. For the Native Americans, it marked the first united multi-tribal resistance to the European interlopers. And as the first of the Indian wars that did not end in complete defeat for the Native Americans, Pontiac’s vision was a clear demonstration of pan-tribal co-operation and would subsequently alter the tactics and strategies of Indian leaders. For the British and American colonists, the conflict resulted in the introduction of new policies that would lead directly to the American Revolutionary War. Pontiac’s Rebellion also bears the dubious distinction of being the first documented and deliberate attempt at biological warfare in North American history. So let us take a brief look at this often overlooked but pivotal episode and its fateful implications.

By the mid-1700s, the Indian Nations of the Eastern Interior were entirely surrounded by invading European powers. When the British fought the French for control of North America as part of the Seven Years’ War, the Native Americans sided with the French whose designs on the Indian lands were limited to the lucrative fur trade rather than colonisation. In 1760, after six years of war, the French abruptly withdrew from the Ohio Valley and Western Great Lakes allowing the British to move in unopposed. Chief Pontiac, however, refused to surrender to the land-hungry invaders who had no interest in cementing friendship with the customs of gift-giving.

By early 1763, Pontiac had succeeded – for the first time in the Indian Wars – in forging a broad coalition of the often inter-warring Indian nations. On 7th May, he launched his initial attack against Fort Detroit. The assault had been anticipated, and the 120-man garrison successfully resisted several attempts by Pontiac. But just two days later, Pontiac’s confederacy attacked isolated settlers outside Fort Detroit and laid siege to the garrison. Within a few weeks other Indian war parties had taken every fort west of Niagara except Detroit and Pitt. Following these stunning victories, by early September, the Indians remarkably stood on the verge of total victory.

But unbeknownst to Pontiac, the French had already signed a treaty of surrender ending all hostilities between the two colonial powers. Freed from campaigns against the French, the British were at last able to give Pontiac’s Rebellion their full attention. And they did so with alarming genocidal-like brutality. General Jeffrey Amherst – the commanding officer of North American British forces – ordered the distribution of amongst the Indians of blankets infested with the deadly smallpox virus. Thousands and thousands of Native Americans were subsequently wiped out by the epidemic.

When confirmation of the French surrender eventually reached Chief Pontiac, it was a decisive blow to the momentum of the rebellion. The British seized the opportunity to end the expensive conflict and make peace. In a delayed attempt at diplomacy, they agreed to establish a line at the Appalachians – beyond which settlements would not encroach on Indian territory. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 stated: “We do strictly forbid, on pain of our displeasure, all our loving subjects from making any purchases or settlements whatever in that region.”

King George III would soon renege on his promise but, of far greater significance, colonists were incensed by the king’s command to establish an Indian-controlled frontier, believing that unlimited westward expansion was their right and destiny. Resentment escalated further when taxes were introduced exclusively to the colonists to finance the defense against the Indians, and the seeds of a plot for a new rebellion began to germinate. When the Revolutionary War broke out, most Indians would fight on the side of their recent British enemy.

As for Chief Pontiac, after the failure to capture Fort Detroit he withdrew but continued to encourage militant resistance to British occupation. Although the British had successfully pacified the uprising, they decided to negotiate with the Ottawa leader in a show of respect. Pontiac met with the British superintendent of Indian affairs in July 1766 and formally ended hostilities. Three years later, on April 20th 1769, he was murdered. It was rumoured that the British hired his assassin.

One Response to 7th May 1763 – Pontiac’s Rebellion