The history of 19th Century female revolutionaries, unsurprisingly, mirrors women’s subjugated status throughout that century. If their stories have not been entirely suppressed or consigned to mere historical footnotes, female revolutionaries have usually been documented by historians as embarrassing radical lunatics, our predominantly male historians selling the image of the heroic freedom fighter and liberator as though belonging to an almost exclusively male domain. One notable exception is Policarpa Salaverrieta, a Colombian revolutionary executed in 1817, by the Spanish overlords of what was then known as New Granada. Unlike so many other brave women whose considerable contributions to the numerous revolutions throughout the 1800s remain anonymous, Policarpa Salaverrieta is Colombia’s most beloved and popular heroine. Images of La Pola, as she is popularly known, have long graced banknotes of the Colombian peso, and the whole population annually honour her memory with their “Day of the Colombian Woman”, an official holiday passed by Act of Congress in 1967. La Pola was not the only female revolutionary during Hispanic America’s long battle for independence from Spain – but her courage and zeal, particularly in the moments before her execution, captured the imagination of Colombians for whom she remains a celebrated, emblematic and ubiquitous Colombian martyr.

The enormous toll taken upon Spain by its war with Napoleon had obliged the ailing empire to keep its military forces close to home, allowing its more distant colonials the opportunity to foment ideas of Home Rule in their absence. And in the far province of New Granada, an independence movement had grown up led by the heroic General Antonio Nariño. By 1817, however, Spain had recovered sufficiently from its Napoleonic war for the new king Ferdinand VII to deploy forces to the New World in order to quash those separatist uprisings. High on the list was New Granada, where the Spanish forces quickly regained control of its capital Bogotá, reinstalling their Viceroy as governor of the colony and suppressing the freedom movement with utmost brutality.

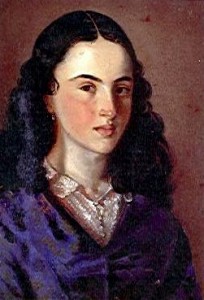

Enter Policarpa Salaverrieta, a beautiful, feisty and fiercely patriotic 26-year-old who, aided by false documents supplied by the resistance movement, gained entrance to the royalist stronghold in Bogotá. Working as a seamstress, she infiltrated the drawing rooms of some of the most eminent royalists, feeding back intelligence that the patriots would never have otherwise been able to obtain. As a pivotal member of the underground resistance, La Pola was also responsible for collecting donated money, procuring military equipment, making uniforms and transporting and hiding soldiers. Always quick to recruit secret patriots from among the many royalist soldiers pressed unwillingly into service, the alluring La Pola would persuade them to desert by providing each one with introductory papers signed by herself, and directing them safely to patriot lines.

In September 1817, the Spanish apprehended two brothers carrying compromising documents implicating La Pola in rebellious activity. Her connection to the revolution was confirmed following the capture of a patriot leader carrying long lists of the names of royalists and rebels bearing Policarpa’s signature. Arrested and condemned to death, she was offered freedom if she recanted. She refused. Her public execution in the main plaza was set for the morning of 14th November. Hands bound, La Pola marched to her death with two priests by her side. But instead of repeating the priests’ prayers as was custom, she cursed the Spaniards and predicted their defeat. So vociferous were the needle-sharp taunts of this erstwhile seamstress that the Spanish governor feared the lesson he was trying to impress upon the large crowd of onlookers would be lost. He gave orders for the drummers to beat louder. But La Pola raved on, admonishing the soldiers for not turning their rifles on the authorities and berating the firing squad for preparing to shoot a woman. “Assassins!” she shouted as she ascended the scaffold. “My death will soon be avenged!”

Due to the testimony of a 19-year-old patriot soldier named Jose Hilario López, we know with certainty that La Pola’s tongue was never silenced right up to her last breath. For that vital witness to her death would eventually rise to become president of the liberated Republic of Colombia. Repeating the story of her bravery throughout his long career, López’s words resound still in the hearts of Colombians. Policarpa Salavarrieta is remembered today throughout Colombia as the “Heroine of Independence”.

8 Responses to 14th November 1817 – Colombia’s Heroine Of Independence: Policarpa Salavarrieta